Decades ago, while working as a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at Oxford’s Institute of Virology and Environmental Microbiology (IVEM), I witnessed the powerful potential of genetic modification to address persistent challenges in agriculture. We were on the cusp of breakthroughs that could help plant breeders combat crop losses caused by pests, diseases, and climate stress.

Our multidisciplinary team, led by the visionary Professor Jenny Cory, worked on integrated pest management systems (IPM) using the baculovirus expression system to develop biological pesticides.

Our goal was clear: to help farmers who regularly faced devastating losses in staple crops like cowpea, cassava, maize, and cotton. These losses often exceeded 50 percent of their harvests.

Fighting hunger means addressing preventable crop losses head-on. Conventional plant breeding methods were falling short, and desperate farmers resorted to chemical pesticides, harming their health and the environment. Genetic modification offered a safer, more effective path—but fear, misinformation and clever anti-GMO campaigns stalled progress.

The question we asked was simple: What is the cost of this fear?

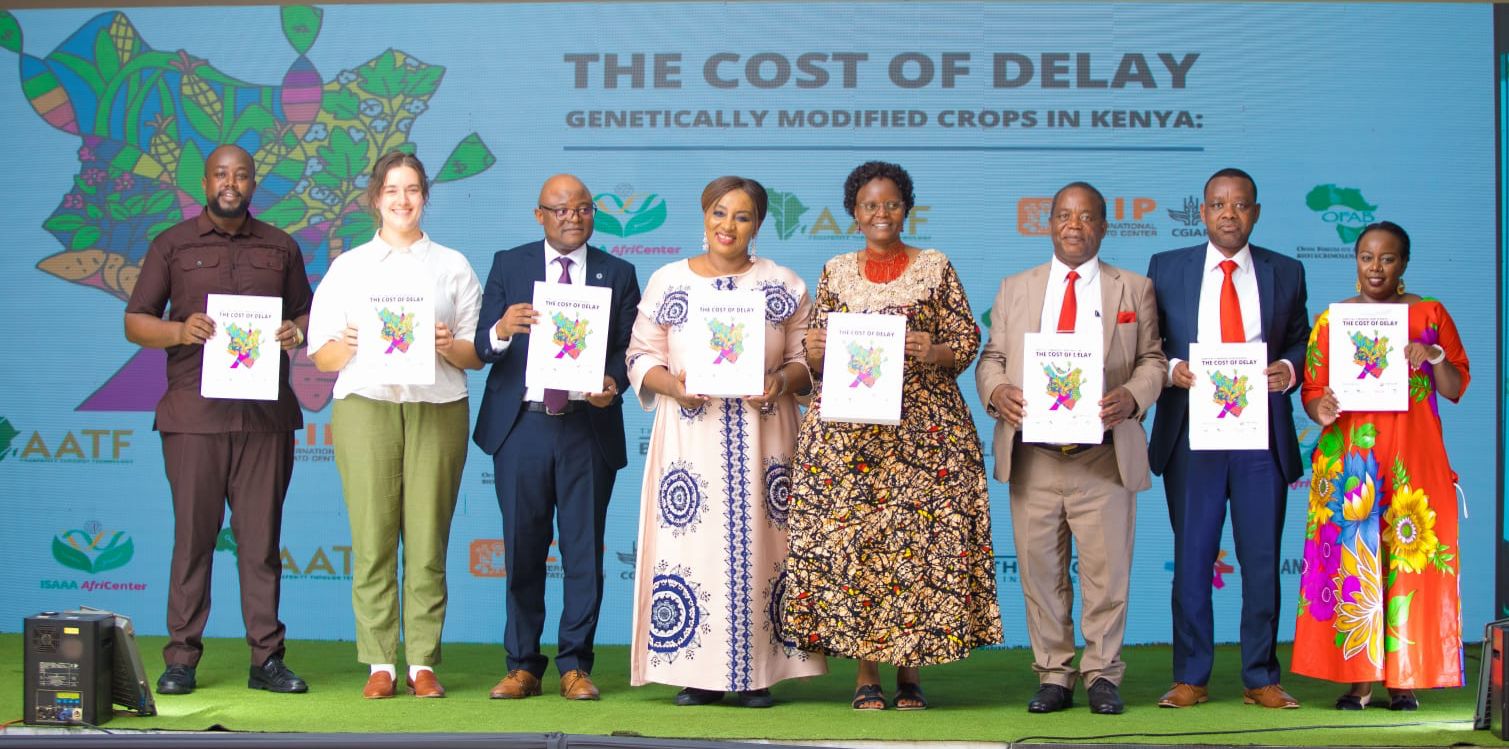

With support from the Breakthrough Institute, Africa Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF), Open Forum on Agricultural Biotechnology in Africa (OFAB), International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-Biotech Applications (ISAAA), and the International Potato Centre (CIP), we sought to quantify the damage caused by delayed adoption of three genetically modified (GM) crops: Bt maize, Bt cotton, and blight-resistant (PBR) potato.

Cost of Delay: 157 million dollars and counting

We found that five years of delay in approving these three GM crops have cost Kenyan farmers and consumers 157 million dollars. This isn’t just an economic burden; it threatens food security, public health, and the environment.

Maize:

- Kenya could have started growing maize in 2019, as the seeds were ready by then and field trials had been completed. However, anti-GMO legal cases mean Bt maize is still blocked in 2024.

- This five years of delay has already cost farmers and consumers 67 million dollars.

- With GM Bt maize, in 2024 Kenya could have produced 194,000 tons of additional maize harvest.

- This equals 25 percent of maize imports received in 2022, and 14 times higher than maize food transfer from the World Food Programme to Kenya in 2023.

Bt cotton

Five years of delay in Bt cotton release cost Kenya 1.2 million dollars.

- Bt cotton could have been released in 2015 rather than 2020. Had this been the case, the country could have produced 650 tons more cotton, replacing 12 percent of imports.

- Bt cotton could have helped revitalize the whole cotton sector, with knock-on benefits for jobs and the wider economy.

Blight-resistant potato

- A five-year delay in the release of potato varieties with resistance genes would cost Kenyan farmers and consumers 89 million dollars.

- If the block is lifted, the benefits over 30 years of GM potato would accrue to 247 million dollars, nearly a quarter of a billion dollars in value to the country.

- Smallholder potato production is important for subsistence farmers, so better harvests improve food and nutrition security.

Better science communication is key

Perhaps our communication as scientists wasn’t effective enough to counter the fear-mongering campaigns of anti-GMO activists. Leading politicians spread wild claims—like GM crops causing women to grow beards—while activist NGOs filed legal cases to stall progress.

Meanwhile, scientists quietly dedicate their lives to rigorous research and risk assessments. Before any GM crop is released, national biosafety agencies ensure regulatory compliance to protect public health and the environment. The process is thorough and evidence-based.

My journey—from lab research to science communication—has spanned 30 years. Change is slow, but it’s coming. Farmers deserve the best tools to protect their livelihoods, and Kenya deserves food security built on science, not fear.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Dr Sheila Ochugboju is the Executive Director of the Alliance for Science.