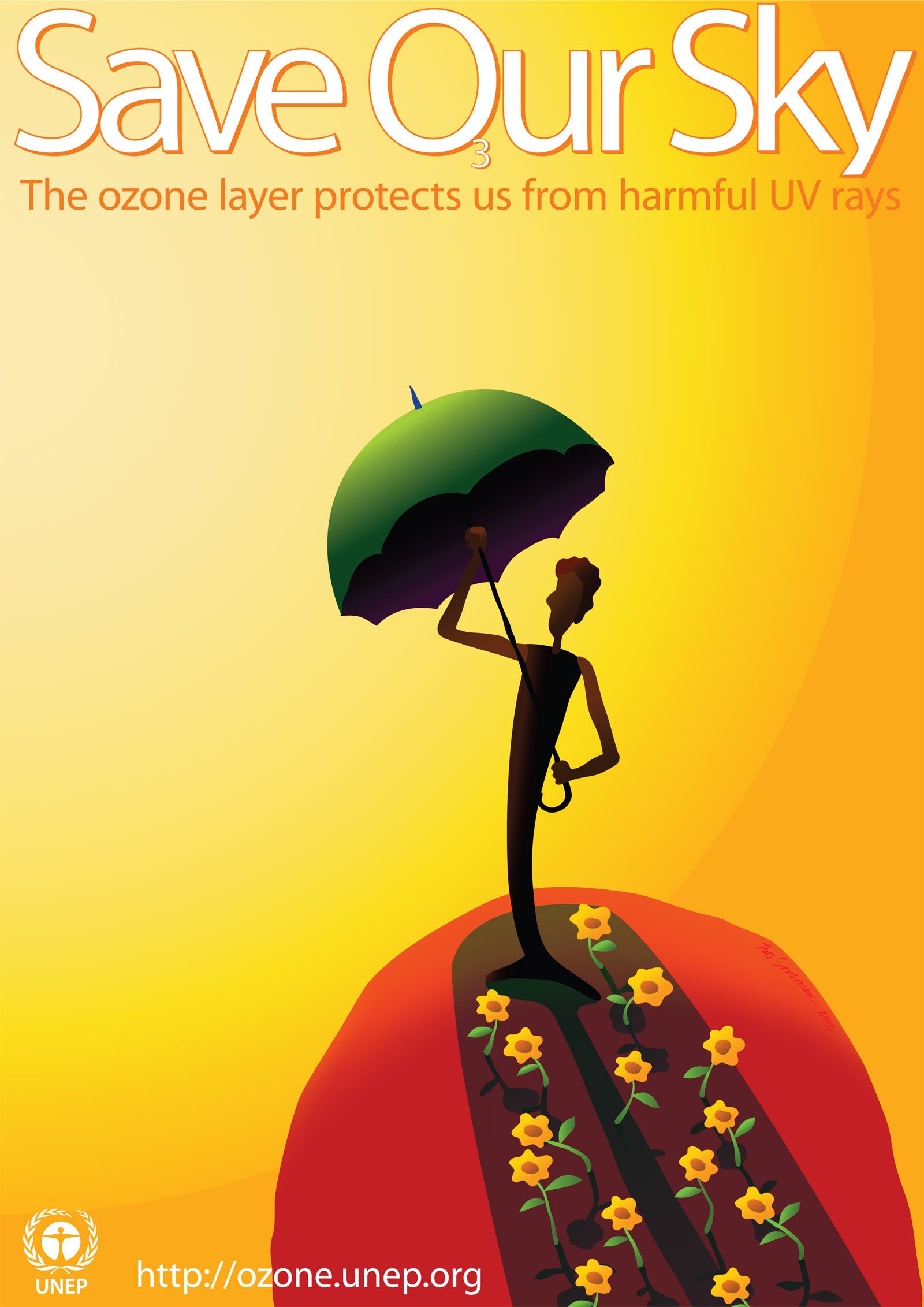

A few miles above the Earth’s surface lies the Ozone layer that protects all life from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays.

The scientific consensus has been that if it did not exist, more hazardous radiation from the sun would enter the Earth’s atmosphere, causing harm to aquatic systems, forests, agricultural fields, and humans.

“The stratospheric Ozone layer is a precious resource that absorbs between 93 and 99 percent of the sun’s ultraviolet rays. However, some measures of human-induced emissions of Ozone-depleting chemicals continue to affect it negatively in some regions,” said Edgar Mcharo, a Tanzanian climate scientist.

“It is why it is important on this year’s World Ozone Day, which was observed on September 16 under the theme Fixing the Ozone Layer and Reducing Climate Change, to remind nations that still produce, emit, and consume substances that deplete the Ozone layer of their commitment to protecting it, as stipulated by the Montreal Protocol,” said Stephanie HaySmith of the UN Environment Programme’s Ozone Secretariat.

“This year’s Ozone Day commemorates the 36th anniversary of the Montreal Protocol and also provides an opportunity to commend African nations that have phased out these substances.”

“This year’s Ozone Day commemorates the 36th anniversary of the Montreal Protocol and also provides an opportunity to commend African nations — except South Africa, which has been getting exemptions to consume methyl bromide — that have phased out these substances.”

Reduce hydrofluorocarbon production

These phase-out efforts are why a UN-backed panel of specialists recently concluded that the Ozone layer is on course to recovery within four decades.

The specialists stated that if current policies remain in place, the Ozone layer will recover to 1980 status (before the appearance of the Ozone hole) by around 2066 over the Antarctic, by 2045 over the Arctic, and by 2040 for the rest of the world.

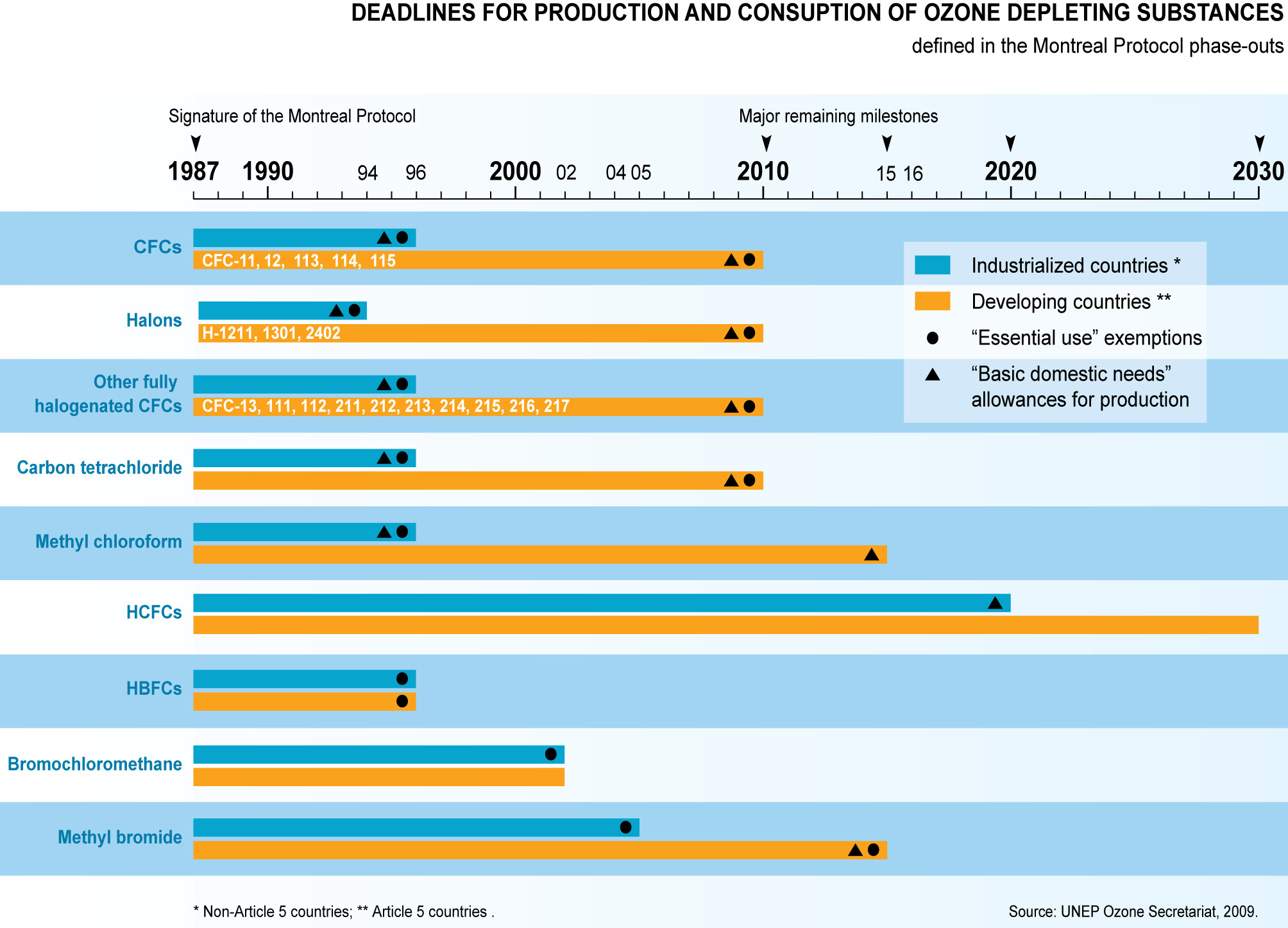

“Since the Protocol’s implementation, 99 percent of Ozone-depleting substances have been phased out in most countries.”

Many global climate scientists concur that the Montreal Protocol, a universally ratified international environmental agreement to protect the Earth’s Ozone layer, has been a game changer.

The Ozone-depleting chemicals that need to be phased out are chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), hydrochlorofluorocarbons found in spray cans, foams, fire extinguishers, air conditioners, and refrigerators; carbon tetrachloride, methyl chloroform, and reactive halogen gases like chlorine and bromine.

“Since the Protocol’s implementation, 99 percent of Ozone-depleting substances have been phased out in most countries,” said HaySmith.

Luke Western, a Marie Curie Research Fellow at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, agreed: “The Protocol has been successful for Ozone recovery and has also avoided global warming.”

“Many African countries have ratified the Kigali Amendment and revised their Ozone depleting regulations and are preparing to start phasing down global warming substances in 2024.”

For African countries, which have recently expressed concern about the dumping of obsolete refrigeration and air conditioning appliances, the most important Montreal Protocol reduction targets have been to phase out chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), halons, methyl bromide, and hydrochlorofluorocarbons.

Ozone-friendly substitutes

“The key obligations for African countries under the Protocol are to have phased out all Ozone-depleting substances except hydrochlorofluorocarbons, which are to be phased out by 2030,” said HaySmith.

“Hydrofluorocarbons or HFCs, introduced in the 1980s as Ozone-friendly substitutes for hydrochlorofluorocarbons and chlorofluorocarbons, come later. They are greenhouse gases but not as bad as those they substituted.”

“Some African nations, however, treaded carefully because eliminating certain Ozone-depleting substances would have occasioned disruptions in some of their development sectors.”

However, the harsh reality of HFCs being greenhouse gases spurred Montreal Protocol countries to propose the Kigali Amendment 2016.

The Kigali Amendment aims to reduce hydrofluorocarbon production and use, and the phasing-out of HFCs could prevent up to 50°C of warming by 2100.

“Under the Kigali Amendment, African countries have to freeze their hydrofluorocarbon consumption in 2024,” said Dr Jos de Laat, a research scientist with experience in atmospheric composition studies and a member of the World Meteorological Organization’s Science Advisory Group on Ozone and Ultraviolet Radiation.

“Many African countries have ratified the Kigali Amendment and revised their Ozone depleting regulations and are preparing to start phasing out global warming substances (hydrofluorocarbons/HFCs) in 2024,” revealed Isaac Mugabi, a Senior Environment Assessment Officer and Ozone Officer at Uganda’s National Environment Management Authority.

However, the indications of African nations’ commitment to phasing out Ozone-depleting compounds showed up early.

African countries have complied

By all accounts, many were well ahead of schedule in meeting their 2010 and 2015 deadlines for the phase-out of chlorofluorocarbons and hydrochlorofluorocarbons.

“Some African nations, however, treaded carefully because the elimination of certain Ozone-depleting substances would have occasioned disruptions in some of their development sectors (horticulture, commercial and industrial refrigeration, and air conditioning, agriculture, and health),” said Mcharo.

“Several African countries have complied, but there have been loopholes at porous borders, enabling the illicit trade in banned Ozone-depleting substances.”

“They to ensure that they reduced their dependency on specific chemicals without negatively impacting their economies, livelihoods, food security, or health.”

Mugabi noted that most African nations had gradually met their Montreal Protocol obligations, with only a few instances of noncompliance to the consumption control measures (the Montreal Protocol includes provisions about Control Measures (Article 2).

“The noncompliant African countries have quickly returned to compliance,” added HaySmith.

“Several African countries have complied, but there have been loopholes at porous borders, enabling the illicit trade in banned Ozone-depleting substances,” Mugabi explained.

Patrick Salifu, the UN Environment Programme’s regional coordinator for the Montreal Protocol in Anglophone African countries, alluded to this illicit trade issue in May this year in Kigali, Rwanda, during a gathering of National Ozone Officers from English-speaking African nations.

Salifu said illegal trade in Ozone-depleting substances in some African countries undermined efforts invested in the Ozone layer recovery.

Being Ozone-friendly also entails taking individual actions to reduce and eliminate its destructive effects.

“The Ozone layer is on track to heal in sub-Saharan Africa by the middle of this century,” said Mugabe, who added that a healthy Ozone layer will lead to a conducive climate, which will lead to the achievement of SDG goals such as SDG 3 which is on good health and well-being and Goal 13 which calls for urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.

Elimination of chlorofluorocarbons

“African nations have to ensure the safe and responsible disposal of Ozone-depleting substances, such as through recycling and safe destruction schemes,” Western said.

“African nations should ensure that they have workable national strategies for phasing out Ozone-depleting substances, operational National Ozone Units that help raise awareness about the illicit trade in Ozone-depleting substances, refrigerant management plans, and investment projects that aid in the elimination of chlorofluorocarbons in refrigeration and air conditioning appliances,” said Mcharo.

He added that being Ozone-friendly also entails taking individual actions to reduce and eliminate its destructive effects.

“Every person can take the lead in ozone layer protection by, for example, reducing the use of vehicles and other devices that release gases containing Ozone-depleting compounds, such as compressors and lawnmowers. People should also learn to use less heating and air conditioning and acquire energy-saving gadgets and bulbs.”

A version of this article appeared in https://www.newvision.co.ug/

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Richard Wetaya is a Uganda-based, award-winning freelance multimedia journalist specializing in science, environment, health, and education reporting.