For close to six decades, Michael Nyaguti has fed on the fish from Lake Victoria in East Africa.

However, he is now skeptical of fish from that lake — which straddles Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania — even when served in his home.

This is because Lake Victoria, where Nyaguti has been fishing for years, is heavily polluted, and he wonders if the fish are fit for human consumption.

Lake Victoria has seen mass fish deaths leading to the loss of millions of dollars in investments and threatening food security in the lake region.

“It saddens me to see what I love doing being threatened by impunity and pollution,” says Nyaguti, the chair of Magnam Environmental Network. This community-based organization is against the pollution of Lake Victoria.

In the recent past, Lake Victoria has seen mass fish deaths, a phenomenon now called fish kills, leading to the loss of millions of dollars in investments and threatening food security in the lake region.

Lake Victoria — Africa’s largest lake by surface area and the world’s largest tropical and second-largest freshwater lake — is the main source of fish consumed in Kenya.

In 2022 and early 2023, local fishers, who rear fish in cages inside the lake, lost up to seven million dollars when thousands of fish died in the cages.

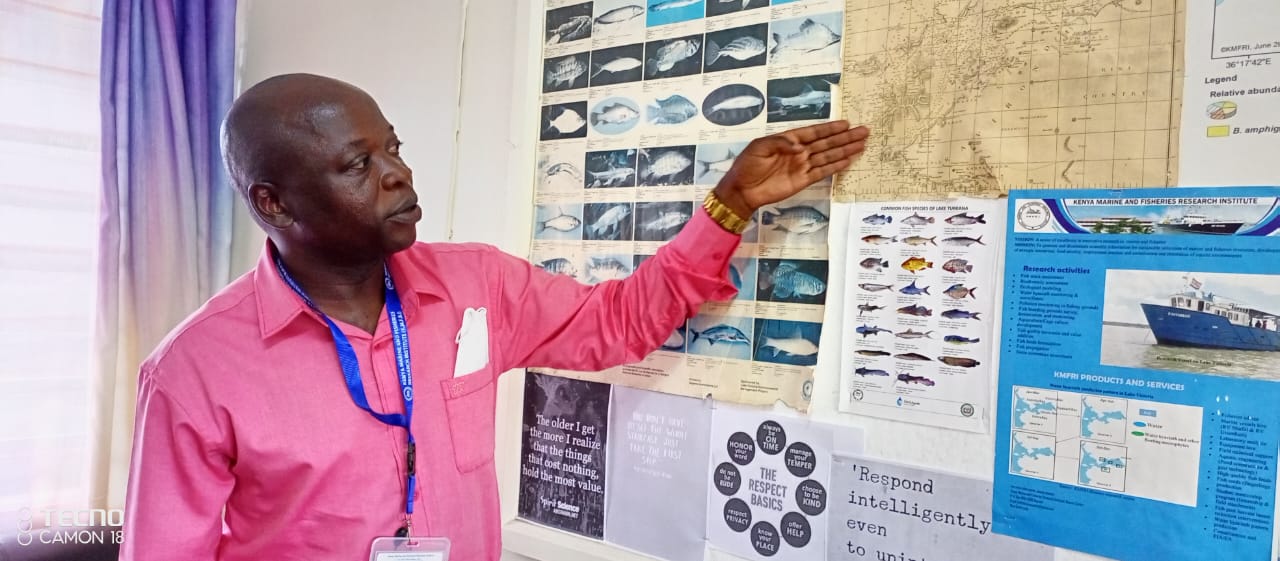

Dr Christopher Aura, the Director of Fresh Water Systems at the Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI), blames the fish kills on the upwelling of the lake.

“Fish die when there is upwelling — the process in which cold water from the deep rises to the surface. Displaced surface waters are replaced by cold, nutrient-rich water that wells up from below,” explained Dr Aura during a media science café organized by the Media for Environment, Science, Health, and Agriculture (MESHA) at Dunga Beach.

The County Government of Kisumu also attributes the fish kills and declining production to the wrong placement of the fish cages and the use of illegal nets by the fishers.

“The mass fish deaths of last year was a lesson on the correct cage location. We now sensitize the fish farmers so they don’t lose their investment,” says Susan Adhiambo, Kisumu County’s Director of Fisheries.

Lake Victoria — Africa’s largest lake by surface area and the world’s largest tropical and second-largest freshwater lake — is the main source of fish consumed in Kenya.

Fish production in the lake has declined from 200,000 tons in 2002 to 98,000 tons in 2022.

According to KMFRI, more than 60 percent of fish production in Kenya and one percent of captured fish globally comes from this lake.

However, fish production in the lake has declined from 200,000 tons in 2002 to 98,000 tons in 2022.

This decline is a threat to food security in Kenya, more so in the lake region where fish is the main source of protein for most households.

According to the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2022, out of the six counties that recorded the highest proportions of households that reported lacking food, three are from the lake region: Vihiga (59 percent), Busia (57 percent), and Homa Bay (57 percent).

Pollution of the lake is making this decline in production worse, with Dr Aura saying it affects the productivity or fertility of the fish.

One of the companies accused of releasing effluent into the lake is the government-owned Kisumu Water and Sanitation Company Limited.

“The lake has the potential to produce 300,000 metric tons annually, but the current annual production on average is about 115,000 tons valued at 85 million dollars on a declining trend,” he says.

Dr Aura attributes the contamination to eutrophication, which is the gradual increase in the concentration of phosphorus, nitrogen, and other plant nutrients in an aging aquatic ecosystem such as a lake.

He says eutrophication is caused by fertilizers, untreated sewage, detergents containing phosphorus, and industrial waste discharge.

As one moves deeper into the lake, the water changes color from clear to dark, then green, and at some point, it produces a pungent smell.

At the mouth of River Kisat, one of the many rivers draining into the lake, the pollution is apparent — plastic and other substances strewn on the smelly water.

According to Nyaguti, all this results from poor waste management that his network has been fighting for several years.

“Water hyacinth moved from this area long ago, so even if it was rotting, that should have stopped by now.”

He blames it on factories operating in the lake region, including some multinational corporations.

Nyaguti says the river washes run-off water and waste from the informal settlements of Obunga, Bandani, and Mamboleo in Kisumu City as it flows toward the lake.

“We argued that a large amount of the waste in this river is removed from the water by the wetland.”

He disagrees with KMFRI that the color and smell of the water are only a result of the algal bloom caused by rotting water hyacinth.

“This is where we differ with KMFRI. Water hyacinth moved from this area long ago, so even if it was rotting, that should have stopped by now. Whatever little that was sedimented should have rotten long ago,” says the environmental activist.

Adjacent to the lake at the mouth of River Kisat is a golf course. Nyaguti says the course management wanted to expand it towards the wetland area, but he went to court, and the move was stopped.

However, the wetland is being cleared, and the golf course is expanding towards the lake.

“We argued that a large amount of the waste in this river is removed from the water by the wetland. So, the court ordered that any establishment be at least 60 meters from the riparian area,” says Nyaguti.

Ironically, one of the companies he accuses of releasing effluent into the lake is the Kisumu Water and Sanitation Company Limited (KIWASCO), a government-owned water treatment and supply firm.

But Thomas Odongo, the KIWASCO managing director, says they only release treated water into the lake.

He says the two primary sources of phosphates in the lake are soaps used by residents and artificial fertilizers from surrounding farms.

He says KIWASCO’s two treatment plants beside River Kisat and Nyalenda Estate can handle domestic and industrial waste.

“They are not sewage-treatment plants but water resource recovery centers where we recover the wastewater, treat it, make it environmentally friendly, and release it back to the water bodies,” Odongo says.

“Waste that comes from treatment plants is minimal. We need to deal with the source of the phosphates. Everyone in the Lake Region Economic Bloc is responsible for the pollution.”

Odongo says KIWASCO is acquiring a compact waste management system to improve its capacity and better fight the contamination of the lake.

The contamination continuously denies Kenya more than 280 million dollars in annual revenue.

Despite all the assurance, Salim Abdala, a local fisherman and the Kichinjio Beach Management Unit co-chair, says they often see dead fish washed to the shore and are worried about what the future holds for their primary food source.

In the meantime, Dr Aura says the contamination continuously denies Kenya more than 280 million dollars in annual revenue.

For Nyagut, Abdala, and other fisherfolk, their primary source of living and nutrients is under threat.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Ombogo is an editorial consultant and consulting science editor for Media for Environment, Science, Health and Agriculture (MESHA) in Kenya.