Three years ago, the world was in the firm grip of the Covid-19 pandemic which has killed more than six million people globally.

Many nations allocated resources to fighting the pandemic and almost ignored another crisis, climate change, whose consequences should not be downplayed, especially in Kenya which is recovering from a drought.

The future economic costs of climate change are uncertain.

However, aggregate models indicate that by 2030, the net economic costs could be equivalent to a loss of three percent of Kenya’s GDP each year.

This is because Kenya’s economy is climate-sensitive, with agriculture, water, energy, tourism, and wildlife sectors being important.

Climate finance disproportionally targets the renewable energy sector, while other key sectors, like agriculture, forestry and land use, transport, and water management, are underfunded.

In the longer term, United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) estimates that by 2050, the cost of adapting to climate change across Africa could reach 50 billion dollars a year.

Under a stabilization scenario, the aggregate models report a 2ºC temperature rise target that could avoid the most severe social and economic consequences of these longer-term changes. This emphasizes the need for climate financing and global mitigation.

On January 9, 2023, Kenya established a State Department for Environment and Climate Change under the Ministry of Environment to underline the government’s commitment to protecting Kenya from the adverse effects of global warming.

This order signals that taking action to adapt to and mitigate climate change is of national interest.

The challenge however lies in Kenya’s approach to climate-related investments.

Kenya’s agricultural sector contracted by 1.5 percent in the first half of 2022.

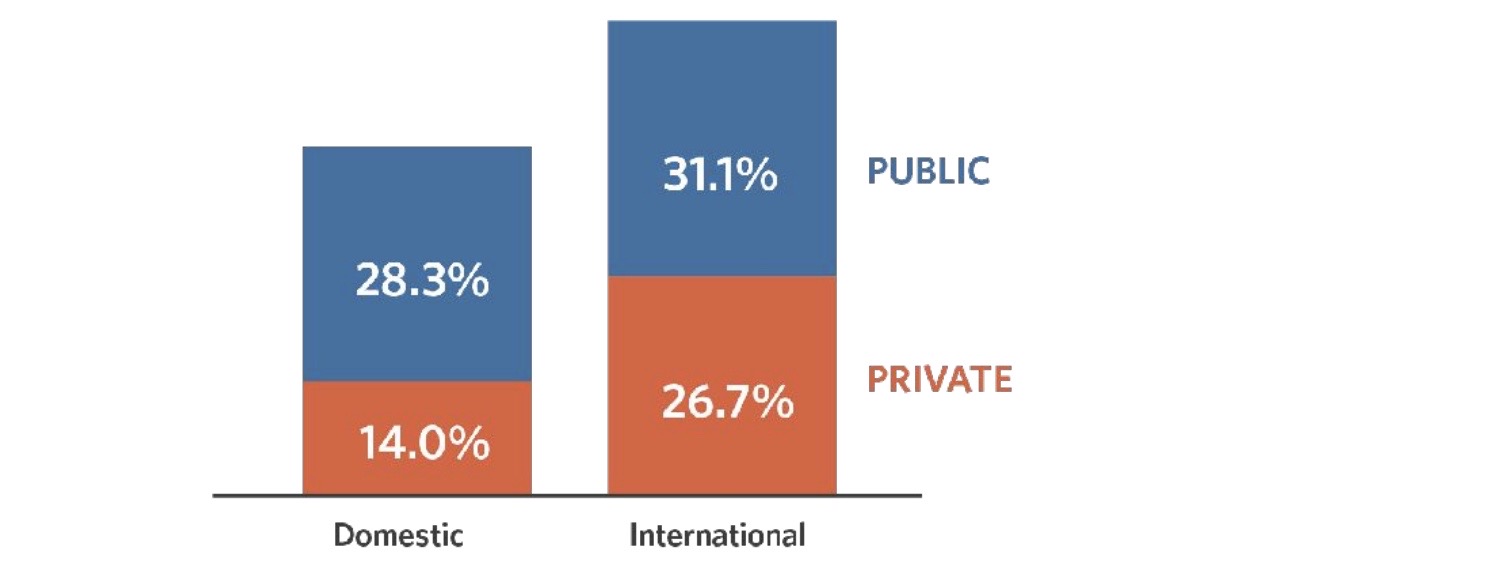

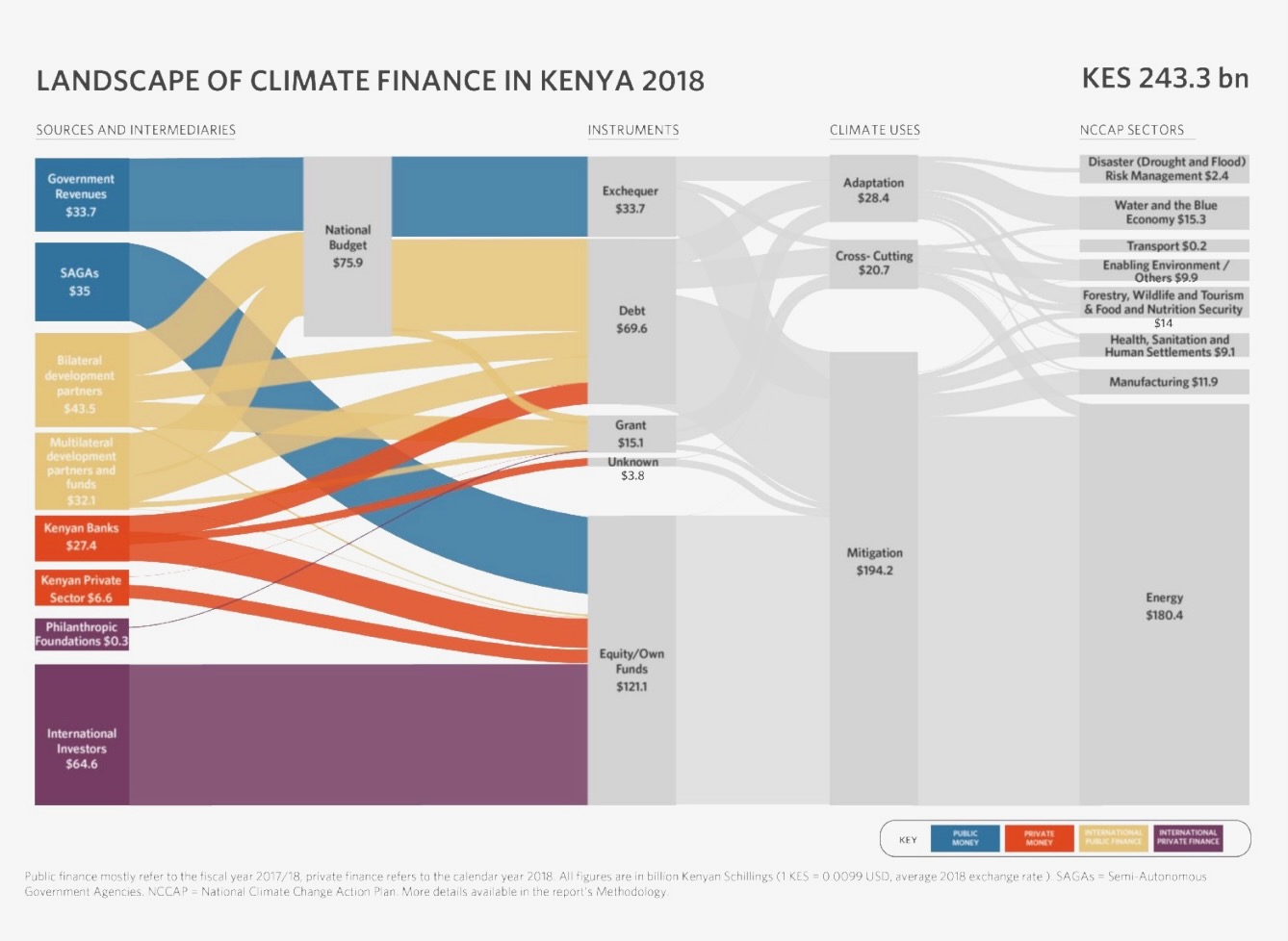

In 2018, 2.4 billion dollars flowed to climate-related investments, one-third of the finance needed annually.

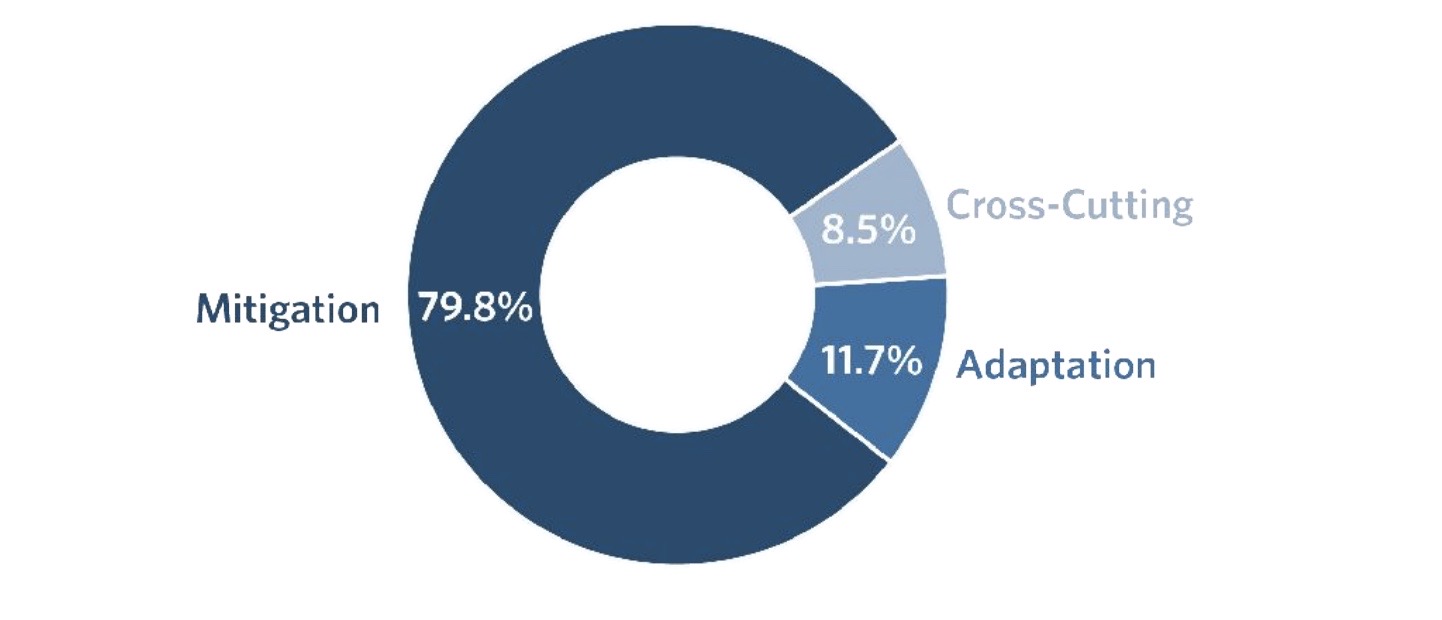

Slightly more than 79 percent of these funds were directed to implementing climate mitigation measures, which starkly contrasts the need given that Kenya has an adaptation-focused strategy.

This presents an economic risk due to the country’s cost of climate events such as drought and famine.

Climate finance disproportionally targets the renewable energy sector, while other key sectors, like agriculture, forestry and land use, transport, and water management, are underfunded.

The National Treasury reiterates that the current financing disproportionately targets certain sectors that will only partially address climate issues and significant efforts will be needed to align all sectors.

Agriculture sector

The agriculture sector is central to economic growth, employment, and poverty reduction, but productivity growth and value addition in the sector have been elusive.

The agricultural sector is also the largest source of Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions in Kenya at 59 percent, with livestock-related emissions accounting for more than 96 percent.

The majority of Kenyan agriculture relies on rainfall, with only less than five percent of farms under irrigation, and the sector has suffered from increasing variability in precipitation.

The long dry spell led to a contraction in agriculture output, underlining the vulnerability to climate-related risks and the need to increase resilience to climate change.

Climate change poses an additional challenge to the prospects of the sector putting agricultural production and food security at risk through its impacts on water availability, incidence, and intensity of animal and plant pests and diseases.

The long drought led to a contraction in agriculture output, underlining the vulnerability to climate-related risks and the need to increase resilience to climate change.

Kenya’s agricultural sector contracted by 1.5 percent in the first half of 2022.

The World Bank reports that with the sector contributing almost one-fifth of GDP, its poor performance pulled back GDP growth by 0.3 percent.

As of July 2022, the drought had left 3.5 million people food insecure in Kenya, a 13 percent increase since the February 2022 assessment.

The drought adversely affected outputs of the crops and livestock sub-sectors in the first half of 2022, which in turn reflected in the dismal performance of Kenya’s key commodity exports including tea and horticulture.

As of July 2022, the drought had left 3.5 million people food insecure in Kenya, a 13 percent increase since the February 2022 assessment.

Climate change poses an additional challenge to the prospects of Kenya’s agricultural sector.

Kenya’s climate has been changing over recent decades, increasing the likelihood and intensity of extreme weather events (such as drought and floods).

The economic cost of floods and droughts is estimated to create long-term fiscal liabilities of 2 to 2.8 percent of GDP each year.

Future climate change is expected to bear heavily on Kenya’s food and nutritional security with yield reductions of 40 – 45 percent expected for maize, rice, soya bean, coffee, and tea by 2050, and an increase in food prices by 75-90 percent by 2055.

Future climate change is expected to bear heavily on Kenya’s food and nutritional security with yield reductions of 40 – 45 percent expected for maize, rice, soya bean, coffee, and tea by 2050, and an increase in food prices by 75-90 percent by 2055.

Poor households in both urban and rural areas spend the majority of their income on food and fuel.

The severe drought also drove the number of children facing acute malnutrition up by 9,539 in June 2022, and there were fears the numbers would rise if the rains failed again.

An increase in food prices, as a result of a reduction in yields will therefore disproportionately affect the poor.

This will in turn necessitate an increase in social protection spending by the government to cushion the poor households.

Health sector

It is evident from a research study by Environmental Epidemiology in 2021 that there exists a positive relationship between climate change and the outbreak of infectious diseases.

Pandemics threaten economic prosperity due to the huge costs required to address their impact.

In Kenya, 67 million dollars was allocated towards Covid-19 vaccinations in FY 2020/21.

The estimated cost of implementing Kenya’s mitigation and adaptation actions stands at 65 billion dollars for the period 2020-2030.

The opportunity cost that would have been derived from this amount is that it was adequate to procure and distribute drugs to the 78 percent of Kenyans on antiretroviral treatment for two financial years or purchase Special Insecticide Treated Mosquito Nets for the prevention of malaria, a leading cause of deaths, whose victims increased from 11,768 in 2020 to 12,011 in 2021.

The money was sufficient to hire health specialists across the 47 counties considering that Kenyan has shortages of chest specialists, hospital physicians, and emergency care nurses.

Investments in renewable energy are essential, but this should not be done at the expense of other key sectors such as health, agriculture, and transport as the trend shows.

The severe drought also drove the number of children facing acute malnutrition up by 9,539 in June 2022, and there were fears the numbers would rise if the rains failed again.

This has cost implications since substantive investments are required to treat stunted growth and investment in education to address grade repetition resulting from the same.

This negative impact on education performance eventually affects social and economic productivity.

The economic impact as a result, of productivity loss was estimated at 6.5 percent of GDP.

All is not lost as scenarios of potential savings also exist.

The estimated cost of implementing Kenya’s mitigation and adaptation actions stands at 65 billion dollars for the period 2020-2030.

To maximize the potential flow of carbon credits, actions must be taken by the government, the private sector, and civil society.

This translates to 4.9 billion dollars annually, of which only one-third was available in 2018.

The huge financing gaps mean that it is critical for the spending to be focused on sectors with the greatest impact.

Investments in renewable energy are essential, but this should not be done at the expense of other key sectors such as health, agriculture, and transport as the trend shows.

If Kenya shifts to a lower carbon pathway, there are numerous advantages.

To maximize the potential flow of carbon credits, actions must be taken by the government, the private sector, and civil society.

Specifically, plans for reducing carbon emissions ought to go beyond the power generation sector.

________________________________________________

Oscar Ochieng is a communications officer at the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA-Kenya).