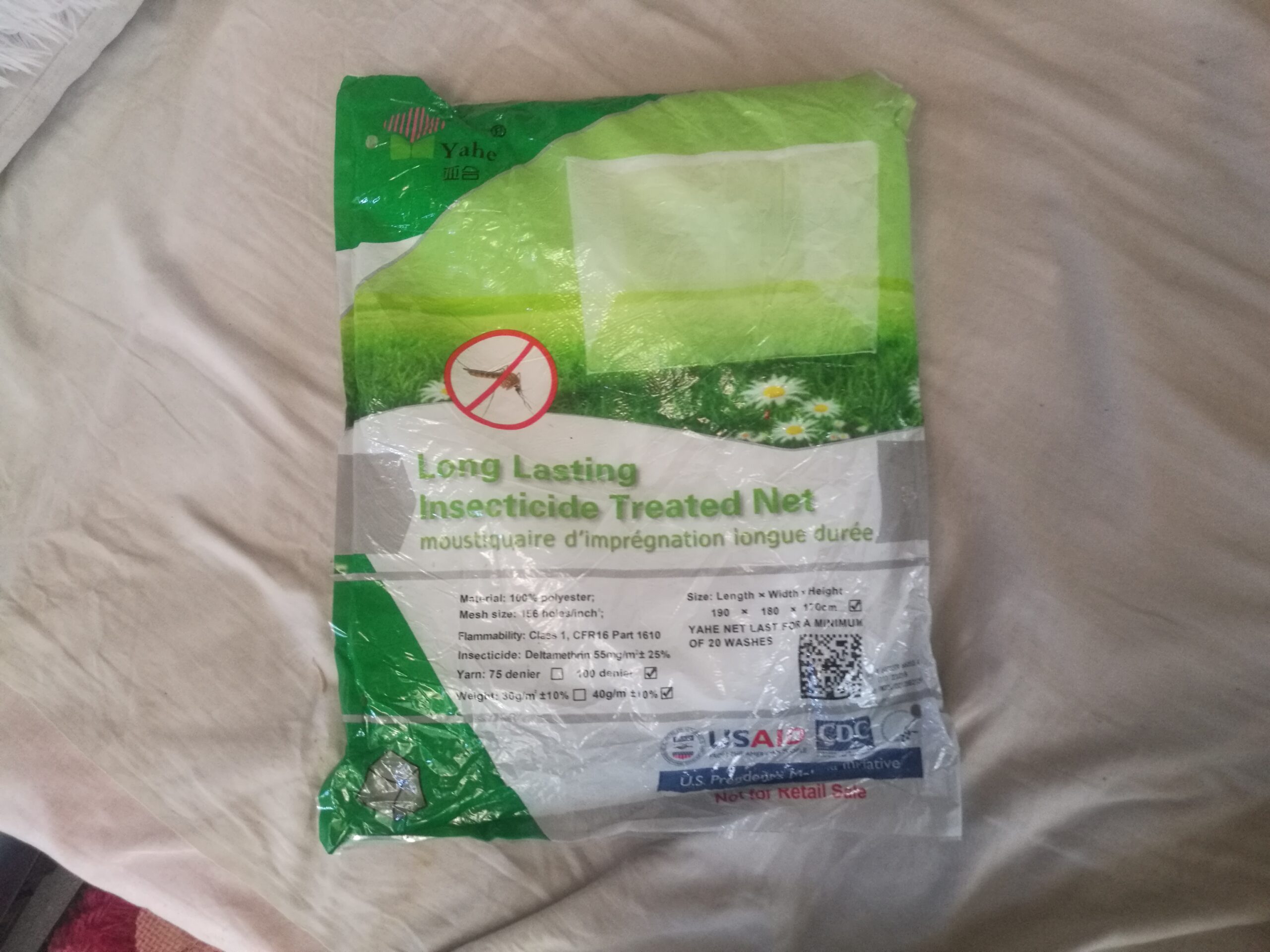

About 100 miles north of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe’s second-largest city, is a hamlet where almost every household has mosquito nets.

School teachers in Lupane own multiple mosquito nets donated by international aid agencies, and they admit that some of the nets are unwrapped, stashed away, and forgotten in their government-provided lodgings.

“Everyone has a mosquito net here in Lupane,” said Sikiniwe Hadebe, a secondary school teacher.

“But what I know is that a majority of the teachers do not make use of the nets because it gets too hot under them. If teachers shun the nets, what about the villagers?”

Healthcare workers, who have been agitating for better working conditions for ages, say dealing with locals is not easy as traditional beliefs still hold sway.

Lupane district lies about 130 miles from the World Heritage site, Victoria Falls, where temperatures can reach 91.4 degrees Fahrenheit, and the stifling night heat forces villagers to ditch their mosquito nets.

No one can monitor if indeed the nets are being used at all or if they are used properly, Hadebe said, adding that a common sentiment is that mosquitoes in Lupane are not the type that transmit malaria.

This sentiment is shared by many residents.

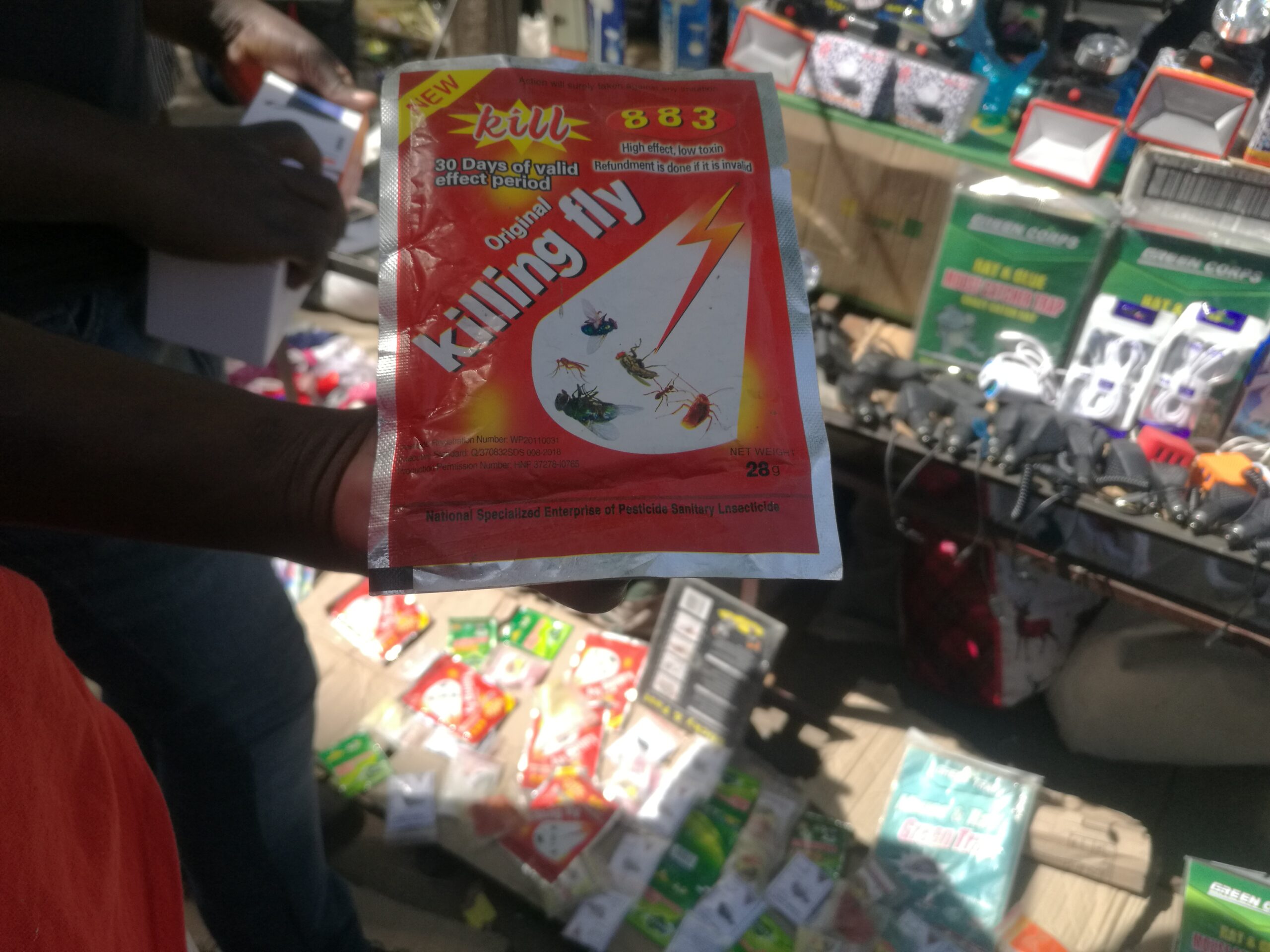

“We do not sleep under the nets. This is a very hot area and a net only makes it worse,” said Thabang Dube, a local businessman who runs a well-stocked odds and ends shop that doubles as a mini-mart and a beer hall.

“We always have our ways of treating fever we suspect to be malaria. The elders know the herbs that work,” Dube said, his sentiments at odds with the public health campaigns from the community clinic next to his shop that tells villagers to sleep under the nets and not take chances with malaria.

According to local researchers, up to seventy nine percent of the Zimbabwe population is at risk of contracting the disease.

Healthcare workers, who have been agitating for better working conditions for ages, say dealing with locals is not easy as traditional beliefs still hold sway.

“It’s always tough trying to convince villagers to practice health safety,” said a nurse working at a rural clinic in Lupane.

“It’s not just about malaria but everything including sexual reproductive healthcare for which they prefer traditional medications. It’s always a work in progress here.”

Zimbabwe’s campaign against malaria has been progressing well, and the aim was to cut mortality to five in one thousand by 2020, with hopes of reducing cases by ninety percent in a country where public health provision has been a challenge for years.

The fight against malaria has also been complicated by climate change, with above-average rainfall providing ample breeding ground for mosquitoes.

However, in an update at the end of March this year, the Ministry of Health and Child Care said thirty nine people had died of malaria since the beginning of the year, and more than 17,000 cases had been reported.

While Zimbabwe has made progress in tackling malaria deaths, home-based diagnosis by families is compromising those gains, especially with the emergence of Covid-19 whose symptoms continue to be confused with those of malaria.

Breeding ground for mosquitoes

A family member hit by Covid-19 is summarily “diagnosed” with malaria and prescribed herbs, effectively slowing down efforts to stem what community health workers term unnecessary malaria deaths.

“As people continued to die from malaria, Covid-19 struck and complicated the efforts to end malaria,” said Itai Rusike, Executive Director of the Community Working Group on Health (CWGH).

“The fight against malaria must remain a priority to protect the progress made to defeat it. This calls for investments in education, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Key to fighting malaria is building stronger health systems,” Rusike added, at a time Zimbabwe’s healthcare system heaves under several challenges including low morale among workers.

According to local researchers, up to seventy nine percent of the Zimbabwe population is at risk of contracting the disease.

The fight against malaria has also been complicated by climate change, with above-average rainfall providing ample breeding ground for mosquitoes.

The fight against malaria has also been complicated by climate change, with above-average rainfall providing ample breeding ground for mosquitoes.

The anti-malaria campaign is part of broader efforts towards meeting Sustainable Development Goal Three which seeks to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.”

Build stronger health systems

With the strained relations between the government and its development partners, community health workers are calling for across-the-board collaboration to deal with challenges such as malaria.

“Community engagement, partnerships with the private sector, the government and the civil society, for mutual planning, execution and accountabilities around malaria programs must be integrated with efforts to build stronger systems anchored on established community health networks,” Rusike said.

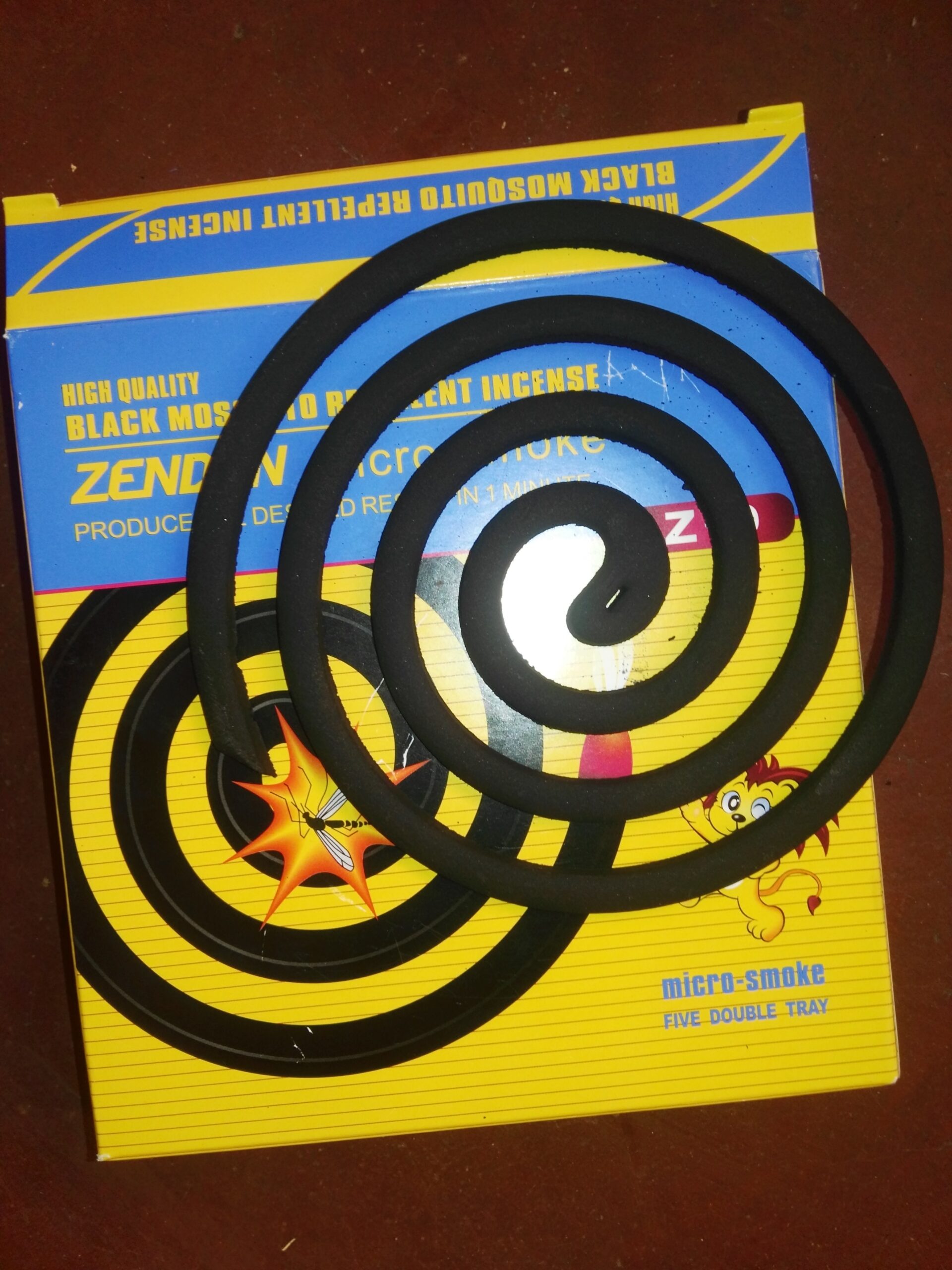

For now, exasperated city dwellers harassed by mosquitoes — which city health officials insist do not transmit malaria — seek refuge in Chinese-made mosquito coils.