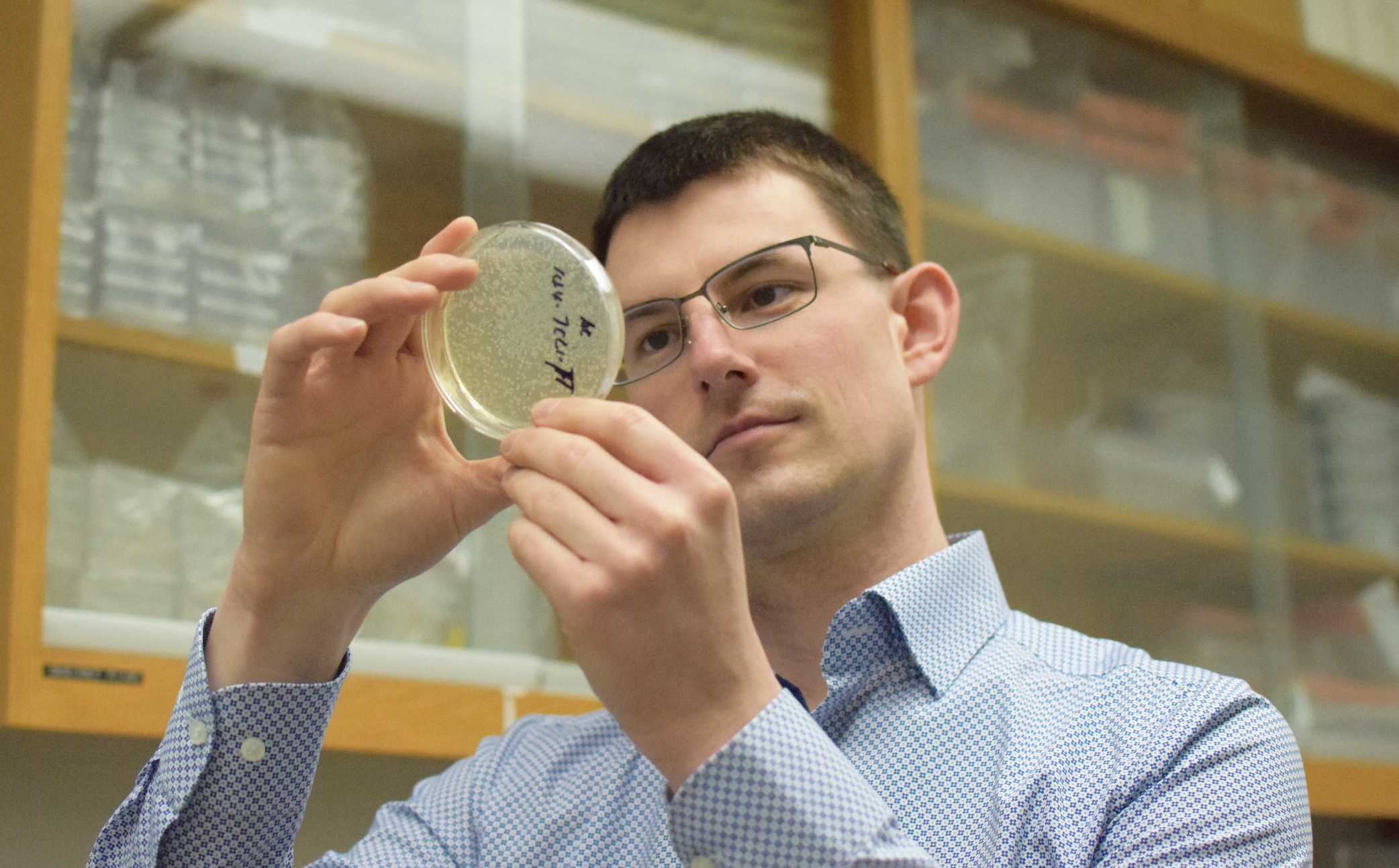

For scientist Simon Sretenovic, seeing was the first step in believing.

As a kid in Slovenia, Sretenovic recalls his elementary school class placing pond water under the microscope to reveal the hidden world within. He was deeply impressed by microscopy and the way that it could reveal things hidden in plain sight.

Now, as a doctoral student, he is pursuing research that he believes can help realize the future of agricultural biotechnology while simultaneously fulfilling his own insatiable curiosity for biology.

Sretenovic’s childhood inspiration carried him through to his bachelor’s degree where he continued tinkering on the microscope. Only this time he was looking at GFP — Green Fluorescent Protein — a naturally occurring protein extracted from jellyfish that glows green under the right light. This protein, a commonly employed tool in many studies of cellular and molecular biology, fast-tracked Sretenovic onto a path of microscopy.

Sretenovic, a Rockey FFAR Fellow, later graduated to an electron microscope where he studied biofilm development in microbes for his master’s degree. This work reaffirmed his desire for what he describes as “organoleptic perception.”

“When you get a really good representative photo it’s a great find,” he said. “Seeing is believing.”

This research also scratched his itch to know how the world around him worked. Growing up, he and his dad, an electrical engineer, would play Legos and build circuits together. He loved the sense of knowing how the building blocks of the world came together and the mechanisms that drove their function.

As a lecturer in Slovenia, Sretenovic continued to explore the realm of possibilities ahead of him. He found his calling when CRISPR came on the scene in a big way in 2012.

“I thought, this is a good technology with tremendous potential for impact,” he recalled.

Putting away his previous need for visual affirmation, Sretenovic took a huge leap of faith and immigrated to the United States to begin his Ph.D. in plant molecular genetics at the University of Maryland, College Park, in the lab of Dr. Yiping Qi.

Here he explores his interests in CRISPR-mediated genome editing in plants. Classic CRISPR applications make use of Cas9 to induced double-stranded breaks in DNA. However, Sretenovic is interested in expanding this tool set to modify plant genomes in novel ways.

He describes the opportunities of future tools as being able to “improve limiting target scope, increase editing efficiency, so you have to screen less plants, and increase specificity.”

One of the tools his work centers on is base editors. Applications of base editors make use of the classic CRISPR/Cas system to home in on a highly targeted region of the genome. However, instead of introducing mutations through double-stranded breaks, base editing allows for the conversion of one nucleotide to another. Most commonly, base editors facilitate transitions from C to T.

Sretenovic sees good scientific tools as seminal for social progress.

“The plants that one could produce with these tools would be easier [than GMOs] to be commercially developed,” he noted, describing traits like elongated grain length in rice as potential targets achievable by base editing.

Sretenovic believes that the future of food will include gene-edited crops.

“In early ages it was traditional breeding, then mutagenesis breeding, then RNA interference and now it is CRISPR technology,” he explained. “It is a natural progression.”

Image: Simon Sretenovic examines rice plants in a research greenhouse. Photo: Dr. Changtian Pan