The world as we knew it ended a few months ago. What we have now is a seemingly alien muddle that we are all trying to make sense of. Aside from occasioning an unprecedented global public health crisis, COVID-19 is a not-so gentle nudge for humanity to rethink—and maybe reset— several things pertinent for our very existence.

Importantly, the pandemic calls us to reconsider a number of facets and realities of our world that, despite their impact, have historically been largely neglected. For example, multiple warnings have been issued about a looming climate crisis. “Looming” is probably an understatement as this crisis is well on course, laying its foundation for destruction around the world.

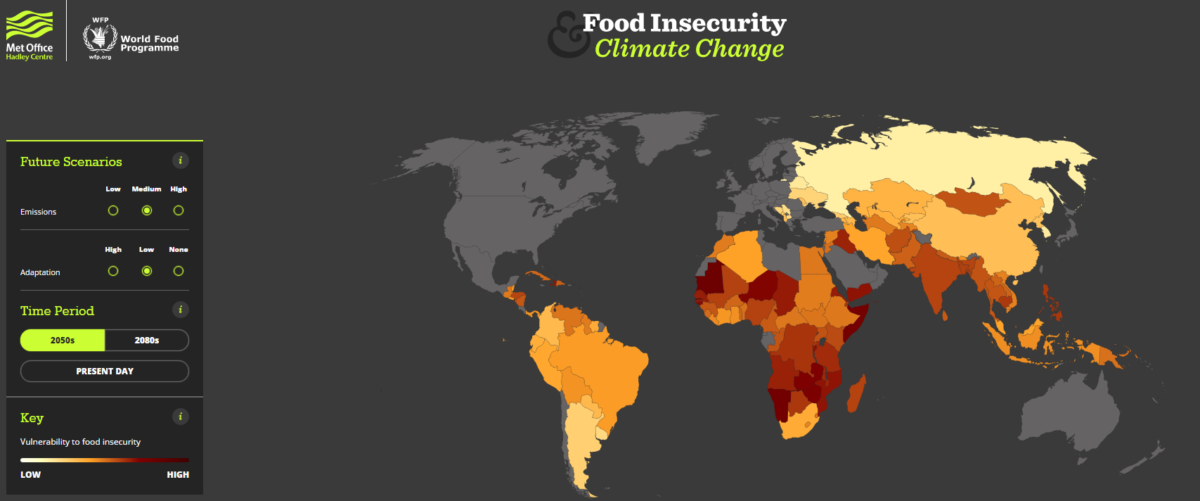

Evidence is mounting on the far-reaching effects of a climate emergency. Important to note is its impact on the global food supply. Erratic weather patterns—increasing drought, floods and rising temperatures—present a growing threat to food production. Agricultural production is projected to be severely compromised by climate change, reducing yields in some cases by up to 50 percent. Recent locust scourges in Africa, reportedly as a result of atypical tropical cyclones, cast more gloom over the fate of African farmers. Such phenomena, along with increasing crises like COVID-19, expose some of the world’s most vulnerable communities to an increased risk of food insecurity and raise the likelihood of a global harvest failure.

At the risk of trivializing the impact of the corona virus, the biggest humanitarian catastrophe—hunger—still looms large. Approximately 9 million people die of hunger annually, albeit without much of a fuss about it in comparison to COVID-19. The pandemic’s current death toll (slightly over 161,000) is only 1.3 percent of hunger’s annual claim. The fact that over 820 million people suffer from hunger today seems to be just a blip on our radar. In a really cynical way, this is probably justifiable; human psychology suggests that we have an uncanny ability to adapt—and gradually ignore—events as they become “old” and less salient in our minds.

Understandably, the current focus is on containing the pandemic. However, it is imperative that we draw fundamental lessons from this pandemic on how we ought to deal with the climate crisis, hunger and any other threats to our survival, for that matter.

Some positives are to be drawn from COVID-19. For starters, science has rediscovered its place as a reliable guide for informed decisions in society. It has become the go-to authority on how to deal with the pandemic as the world turns to scientists to unravel the mystery of this virus. This reverses a decade-old trend of declining trust in credible scientists and institutions. Going forward, the pandemic presents an opportunity for science to play a bigger role in evidence-based policy decisions.

What this pandemic has successfully exposed is how ill prepared we are—especially in isolation—to handle this or the next global crisis. It has highlighted the need for global collaboration to address global challenges like climate change, hunger, etc., which cannot be stopped by lockdowns or border closures. In charting a path forward, we are only as strong as our weakest link. This pandemic reminds us that stronger cooperation and collective action to improve the quality of life everywhere are quintessential.

While on one hand globalization and cooperation are something of a mantra in politics and multinational treaties, geopolitical rivalries and borderline jingoism tend to take the day. Countries and communities have managed to “silo” themselves in effectively shielding themselves from the harsh realities of humanity elsewhere. One wonders if it is going to take a crisis like this pandemic—affecting rich and poor alike—to direct appropriate attention and resources to issues like hunger.

With regard to food/agriculture, this is the perfect moment to break down traditional barriers and dogmas: organic vs GMO, grass-fed vs grain-fed, conventional vs organic, etc. This should be a time when food—conventional/organic/GMO—is marketed and valued for its quality rather than its label; a time when we collectively pursue the greater good of sustainably feeding 7.5 billion people.

Furthermore, despite countless warnings by scientists on the effects of anthropogenic climate change, humans continue to destroy and pollute the natural environment on a huge scale. The world is still far off track to meet the goals of the Paris agreement; some countries have not ratified while others have opted out of the deal. COVID-19 is an aide-mémoire that our health and wellbeing and that of the environment are intricately intertwined.

What ought to happen is the recognition that like the pandemic, climate change is a real threat to humanity that stands to undo a lot of the progress made over the years. We must direct, with the same drive, the collective intellectual, financial, political and social efforts applied in combatting COVID-19 to rejuvenated efforts aimed at reversing the damage we have done to the environment.

If the death toll ascribed to COVID-19 has spurred us into action, then it’s only reasonable to view threats like climate change and hunger with equivalent urgency. Guidelines on what needs to be done to avert the effects of our bigoted obliteration of our only habitable planet are not novel suggestions. The least we can do is listen and act, now! Financing and incentives for a shift to renewable energy, adoption of more sustainable agricultural practices and a renewed sense of environmental stewardship are essential. The need for robust and credible policy mechanisms as well as political will to facilitate such shifts cannot be overstated.

Now is the time to abandon old ideologies and reset—an opportunity to adopt a progressive and pragmatic outlook towards laying the foundation for a safer and more sustainable existence.

Joshua Raymond Muhumuza is an outreach officer for the NEXTGEN Cassava Breeding Project and a science communicator in Uganda.