Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by parasites and spread to humans via infected female Anopheles mosquitoes.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there were about 247 million malaria cases globally in 2021.

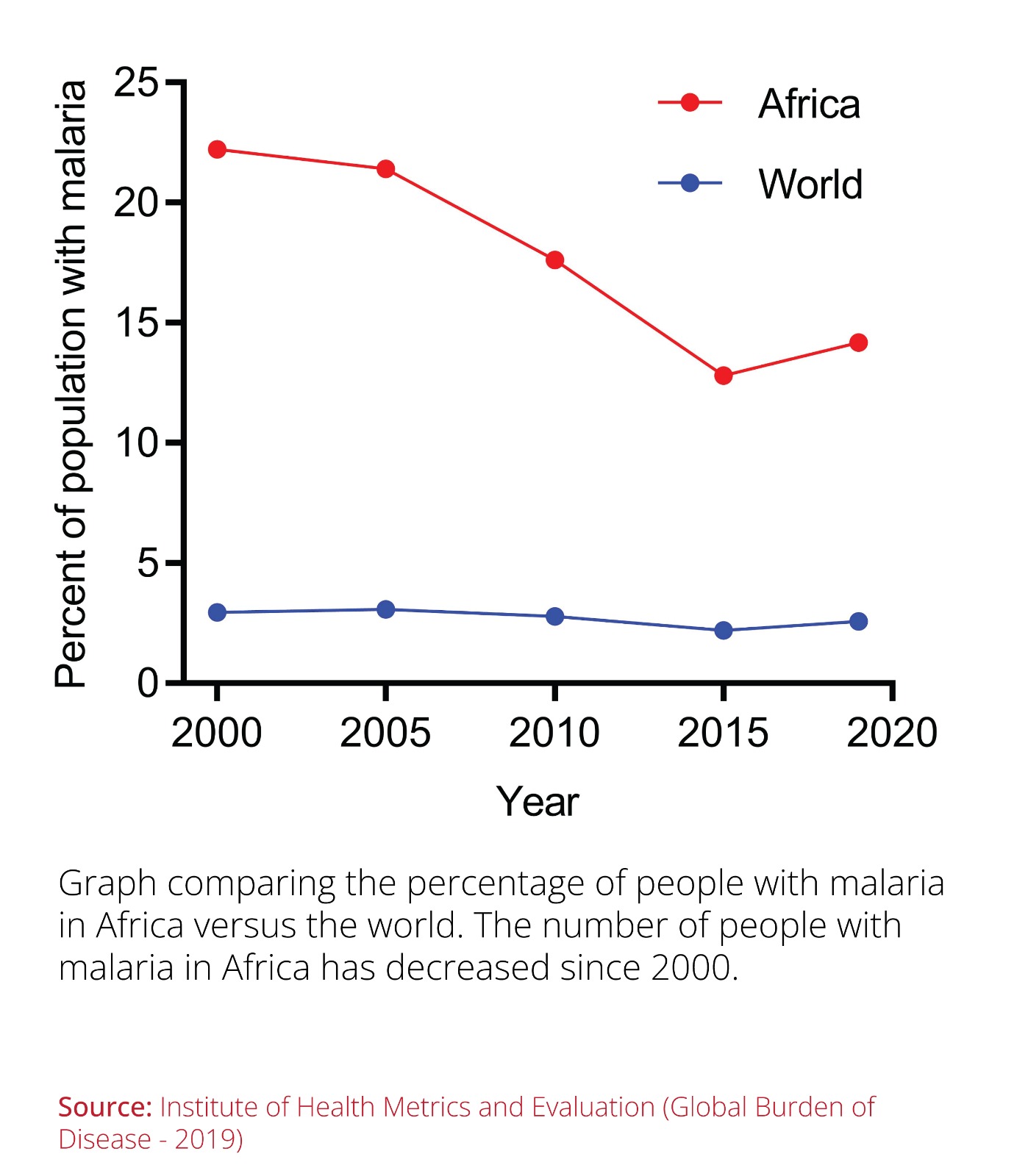

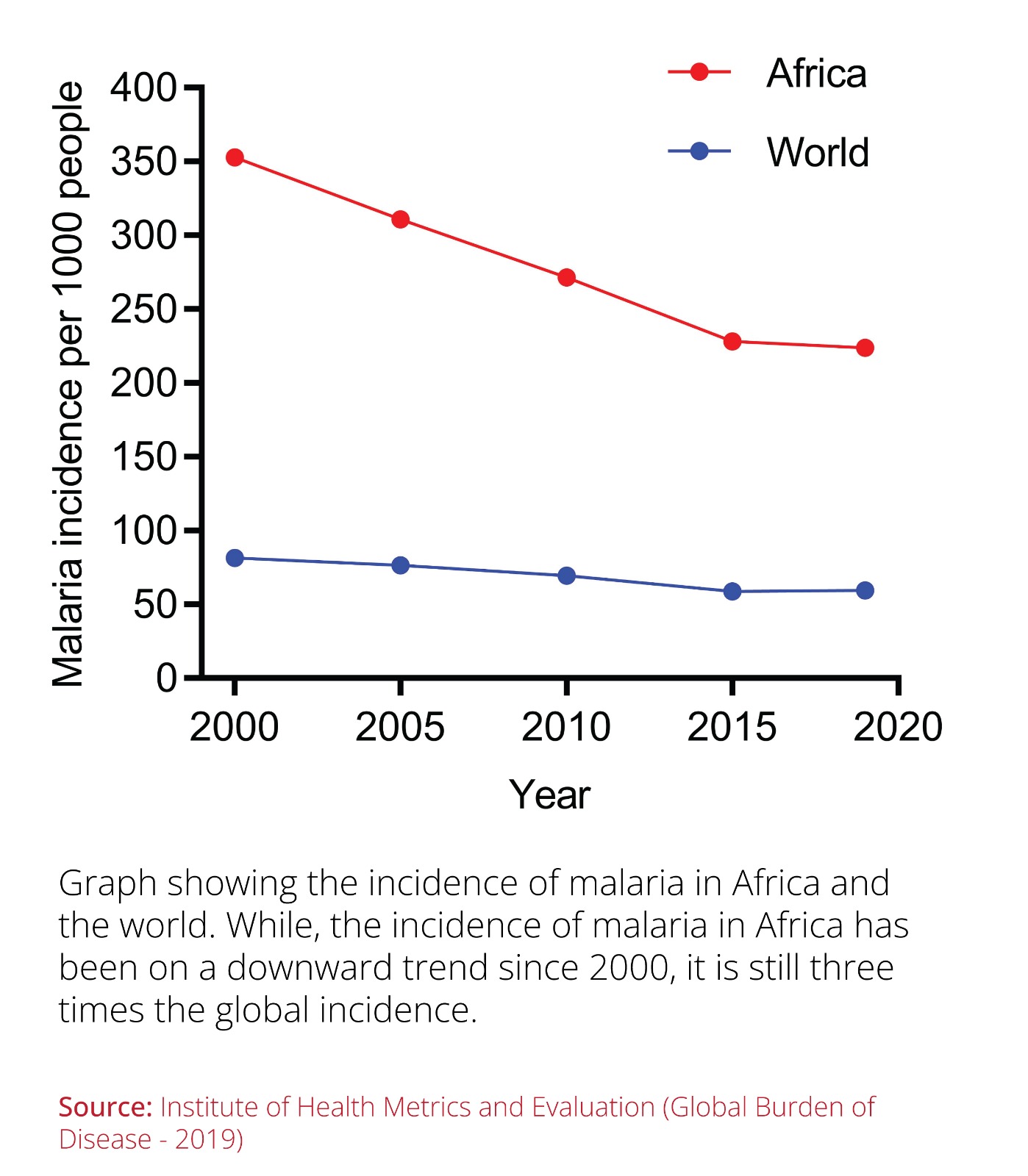

While the global percentage of people with malaria has remained constant over time, Africa carries the highest burden of this disease.

However, it is important to note that the percentage of people living with malaria has been on a downward trend since 2000.

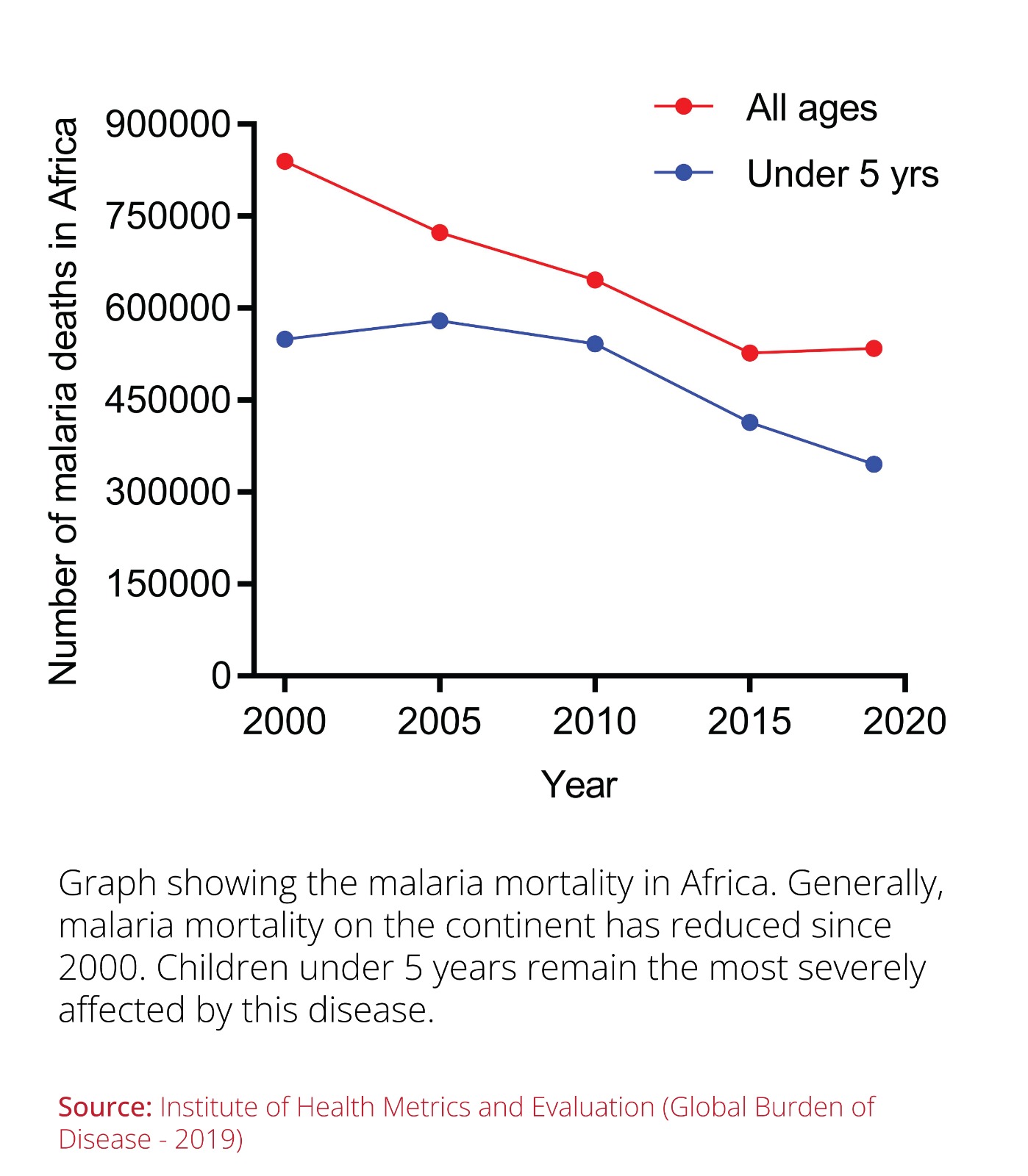

Statistics from 2021 show that 95 percent of malaria cases and 96 percent of malaria deaths were all in Africa, with children under five accounting for 80 percent of malaria mortalities on the continent.

Over the years, we have made impressive progress in reducing the burden of malaria and its associated fatalities because of the development of several malaria treatments and prevention strategies.

These include antimalarial drugs (chloroquine and artemisinin), insecticides against mosquitoes (DDT – dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane), and insecticide-treated bednets.

Treated bednets have been the most effective malaria prevention strategy in sub-Saharan Africa since their introduction in the early 90s.

A long-term study (2004-2019) showed that these treated bednets prevented about 68 percent of malaria cases in sub-Saharan Africa.

Since children aged below five years are the most affected worldwide, we must continue working on the most effective solutions against malaria.

In perspective, over 1.9 billion treated bednets were distributed in sub-Saharan Africa between 2004 and 2019, representing about 36 percent of households covered.

Malaria deaths were reduced over the same period by 27.9 percent from 754000 to 544000 based on the world malaria report published last year.

This is considerable progress, and all stakeholders must be commended for these results.

Since children aged below five years are the most affected worldwide, we must continue working on the most effective solutions against malaria.

While treated bednets were a significant breakthrough in preventing malaria, they also face numerous challenges, including the emergence of resistant mosquitoes.

In 2021, the WHO approved the first malaria vaccine Mosquirix, also known as RTS,S/AS01, developed by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) for children aged between 5 and 17 months at first vaccination.

This vaccine arouses a child’s immune system to act against Plasmodium falciparum, the deadliest of the five malaria-causing Plasmodium pathogens and the most prevalent in Africa.

This vaccine development took over 30 years of research, collaborations, and support from different organizations and stakeholders, including GSK, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome, PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative, the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, governments, and patients.

Why is this vaccine important? Malaria research has many vaccine candidates that were unsuccessful in clinical trials.

While treated bednets were a significant breakthrough in preventing malaria, they also face numerous challenges, including the emergence of resistant mosquitoes.

Against this backdrop, this vaccine is the best development in decades in the fight against malaria and a significant step forward in achieving child health equity.

The pilot vaccination program conducted in Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi showed that this vaccine is safe and feasible to deliver and significantly decreases deadly severe malaria.

If deployed successfully, the WHO estimates this vaccine could save up to 80000 African children annually.

As we wait for the 2023 World Malaria Report, we anticipate finding out the actual effect of this vaccine since its global rollout in 2021.

Once vaccinated, children’s immune system recognizes the parasite’s and the virus’s proteins and makes antibodies against them to protect against future natural infections.

An advantage of this vaccine over prevention strategies is that most countries have established and reliable childhood vaccination programs against other fatal childhood diseases.

This vaccine will be an additional injection that children will get as part of the routine immunization.

Mosquirix vaccine is given as an injection into the thigh muscle or around the shoulder. The child receives three doses one month apart, with the fourth dose recommended 18 months after the third dose.

The active ingredient in this vaccine consists of surface proteins of Plasmodium falciparum parasites and the hepatitis B virus.

Once vaccinated, children’s immune system recognizes the parasite’s and the virus’s proteins and makes antibodies against them to protect against future natural infections.

As we mark World Malaria Day, we should collectively appreciate the ongoing efforts to prevent and manage malaria.

After a bite from an infected mosquito, malaria parasites enter the blood and travel to the liver, where they can mature and multiply.

This vaccine thus limits the capability of these parasites to develop in the liver and cause malaria.

Mosquirix vaccine is the first among many malaria vaccines in the pipeline.

Data from phase 3 clinical trials show that the 3-dose vaccine regimen has a 68 percent protection efficacy over six months.

The fourth booster dose, given 18 months later, demonstrated 44 percent efficacy against the malaria parasite.

These are clearly below the WHO target of developing a malaria vaccine with at least 75 percent efficacy.

Given these low efficacy numbers, we must develop new vaccines to fight malaria.

Currently, about 29 active vaccines against malaria are being tested globally in 77 clinical trials (17 in Phase I, 10 in Phase II, and one each in Phase III and IV).

Currently, about 29 active vaccines against malaria are being tested globally in 77 clinical trials (17 in Phase I, 10 in Phase II, and one each in Phase III and IV).

Of the 29 active vaccines, 24 are against Plasmodium falciparum and five against Plasmodium vivax. One of the vaccines showing promise is the R21/Matrix M1 developed by the University of Oxford, which is currently in phase III clinical trials.

Published findings from a clinical trial in Burkina Faso showed that the 3-dose vaccine regimen had 77 percent efficacy in African children over a follow-up period of 12 months.

A malaria-free world creates a safe environment for child development and frees up resources that can be redirected to meet other public health needs.

A booster dose given one year after the initial 3-dose regimen maintained high efficacy against malaria parasites and continues to meet the WHO target of over 75 percent vaccine efficacy.

As we mark World Malaria Day on April 25, we should collectively appreciate the ongoing efforts to prevent and manage malaria.

A malaria-free world creates a safe environment for child development and frees up resources that can be redirected to meet other public health needs.

Controlling malaria will directly lift communities and countries out of chronic poverty on a continent where malaria consumes up to 25 percent of household incomes and 40 percent of government health spending.

While other malaria vaccines are 5 to 10 years away, we must leverage the current strategies we have in the fight against malaria.

________________________________________

Dr Oria (PhD) is a Cancer Biologist at Biotech Research and Innovation Centre in Copenhagen, Denmark.