Despite the billions of dollars of development aid injected into Africa, poverty, disease burden, and inequality are still rampant.

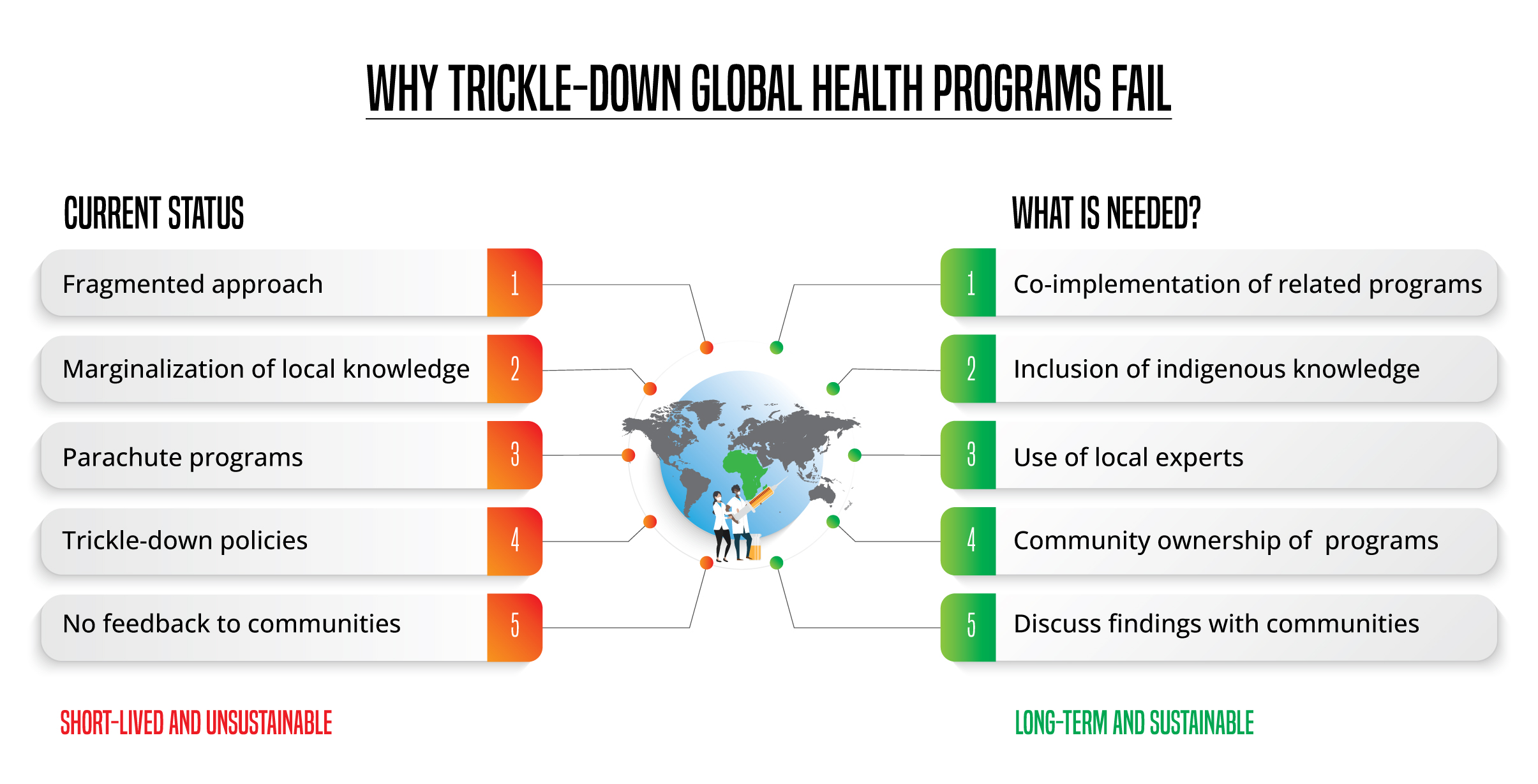

Despite the deficiencies of trickle-down development, global health programs implemented in the Global North have adopted a similar trickle-down approach.

These approaches presuppose that programs developed for populations in wealthy nations will have the same effect in the Global South.

Regardless of the vast resources collectively invested in global health in sub-Saharan Africa, our health systems are still weak.

While these trickle-down programs may have succeeded, they are often short-lived and unsustainable because they do not consider the economic, social, and cultural context they are implemented.

Regardless of the vast resources collectively invested in global health in sub-Saharan Africa, our health systems are still weak, and our health indicators need to be improved.

In 2021, 38.4 million people globally lived with HIV, with about 25.6 million (66 percent) in sub-Saharan Africa.

In the same region, women and girls accounted for 63 percent of all new HIV infections in 2021.

In one of its briefings in 2005, the International Labor Organization reported that there is a circular link between poverty and HIV and Aids.

Around the world, HIV infections are amplified by food insecurity, sexual exploitation, water scarcity, homelessness, substance abuse, and other social inequalities.

For HIV prevention programs to be effective and sustainable, we must address the social inequalities that lead to an increase in infections.

While we have made remarkable progress in testing, tracing, and treating HIV, it is a zero-sum game if we do not tackle poverty.

This is because the main driver of HIV infections has more to do with social inequalities than the virus alone.

For example, in 2021, Kenya reported an increase in new HIV infections with 34540 new cases.

Of these new infections, 52 percent were in young people (15-29 years), an age group suffering from high unemployment rates and thus lack of prospects, substance abuse, and high-risk sexual behaviors nationally.

This correlation is too strong to ignore. For these HIV prevention programs to be effective and sustainable, we must address the social inequalities that lead to an increase in infections.

Many global health programs are not tailored to meet the needs of the target country or different regions within the country.

In most cases, these programs are guided by ideas developed by scientists and public health experts in the Global North or international organizations.

Global health research is still led by researchers from high-income countries in the Global North conducting studies or implementing programs in the Global South.

There is a need to appreciate that global health programs do not work in a silo.

These programs tend to ignore local innovation hubs, scientists, and development experts, and never meet the needs of the end-users in the target communities where they are implemented.

Many trickle-down global health programs follow the academic model of research.

As such, the appetite to identify ‘universal truths’ in this area is probably a disservice to the Global South as it marginalizes crucial local knowledge.

This marginalization stems from pre-existing biases which disregard indigenous knowledge, display hierarchical assumptions, and refuse to learn from the local people.

We need respectful dialogues between the parties involved, including governments, funders, communities, public health experts, academics, and policymakers to make these programs work.

In most cases, global health research is still led by researchers from high-income countries in the Global North conducting studies or implementing programs in the Global South.

The devotion, time, and financial resources that go into these projects are immense.

More important are the millions of people participating in these studies or programs to make a difference.

The biggest letdown is that the communities or people involved in these programs are unaware of the findings.

This non-reporting back to communities that get involved makes them feel like unglorified data points.

Communal ownership of these global health programs will facilitate local knowledge that matches the realities on the ground.

This issue is not novel to global health but a behavior inspired by traditional scientific research, which barely communicates its findings to the public.

What is the way forward? Most global health programs in the developing world focus on public health initiatives such as combating HIV and Aids and other infectious diseases.

Existing evidence informs us that communities suffering from these diseases are usually the poorest.

Therefore, even as these programs provide the needed diagnostic and treatment services, they must be co-implemented with poverty reduction programs.

Otherwise, these new infections will never end.

As a native of the Lake Region in western Kenya, I have experienced the impact of HIV and Aids on communities.

The idea that someone based in the Global North can solve problems in rural sub-Saharan Africa without visiting these communities is unrealistic.

In 2018, this region still had a higher HIV prevalence than the rest of Kenya, a trend that has persisted for two decades.

A 26-year longitudinal study on the global disease burden showed that two counties in this region (Homa Bay and Migori) still have the highest health risk factors associated with HIV despite the massive investments to curb new infections.

These risk factors are related to socioeconomic status and reiterate the need to co-implement HIV and poverty programs.

Second, parachute global health initiatives must end. The idea that someone based in the Global North can solve problems in rural sub-Saharan Africa without visiting these communities is unrealistic.

Global health programs must involve community members as project leaders, principal investigators, and data collectors.

Moving forward, we need to see local ownership of these programs to benefit end-users. Communal ownership of these programs will facilitate local knowledge that matches the realities on the ground.

In addition, these programs must involve community members as project leaders, principal investigators, and data collectors.

Why is this important? Most of these communities suffer from a phenomenon termed research fatigue due to participation in many studies.

Therefore, they refuse to participate in new studies because they never get any benefit.

When members of these sampled communities head these programs, they must report the findings to the community.

This way, communities will appreciate the value of global health programs.

__________________________________

Dr Oria (PhD) is a Cancer Biologist at Biotech Research and Innovation Centre in Copenhagen, Denmark.