A new study suggests that extensive agricultural use of glyphosate herbicide is to blame for the decades-long decline in North America’s monarch butterfly population.

However, international monarch expert Anurag Agrawal, who did not participate in the study, cautioned that the situation is more complex than the study suggests and said monarchs are experiencing stress from multiple sources.

The study, carried out by Monarch Watch and published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, claims to refute previous research that instead pointed to high mortality rates during the butterflies’ annual winter migration as a primary cause for the monarch’s rapidly-falling numbers.

Monarch Watch tagged nearly 1.4 million monarchs in the Upper Midwest between 1998 and 2015. Some 14,000 of those tagged butterflies were recovered in their winter home in Mexico and the tagging recoveries showed “no disconnection between late summer and winter population sizes.” Nor did recovery rates decrease over time.

‘On the wrong track’

According to Monarch Watch Director Chip Taylor, the study’s results thus undermine what is known as the “migration mortality hypothesis” — the belief that the decline in the monarch population is due to increasing perils along the butterflies’ long annual winter journey to Mexico. Taylor said the results instead bolster the “milkweed limitation hypothesis.” This theory points to the widespread use of glyphosate as the main cause of the population decline.

Glyphosate is used on most conventionally grown crops to control weeds and reduce tillage, as well as in roadside and ditch maintenance. Its application has contributed to the loss of milkweed, the only source of food for monarch caterpillars, as has roadside mowing.

“Monarch Watch has been collecting recovery data for tagged monarchs since 1992, and we knew that those advocating the migration mortality hypothesis were on the wrong track from the outset and told them so,” Taylor said in a press release issued by the University of Kansas, where the project is based.

Monarch Watch said the results of the study support calls by scientists and conservations to restore more than a billion milkweed stems in the Upper Midwest. A 2017 study from the United States Geological Survey said that over 860 million milkweed stems were lost in the northern US over the past decade and that nearly two billion additional sets of milkweed would be needed for the Eastern migratory population of the monarch butterfly to rebound to a sustainable level.

“Increasing milkweed habitat, which has the potential of increasing the summer monarch population, is the conservation measure that will have the greatest impact,” the Monarch Watch study states.

‘Naively painting a picture of black or white’

Although the Monarch Watch study in many ways confirms what has been conventional wisdom for years, albeit a theory that is frequently challenged, one of the world’s foremost experts on monarch butterflies cautioned that the population decline is not an either/or proposition.

“The authors attempt to dichotomize the cause of monarch population declines as either due to milkweed limitation or migratory mortality. This is naively painting a picture of black or white,” Agrawal, a Cornell University professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and the author of Monarchs and Milkweed, said. “Unfortunately, it is hardly a dichotomy, and there are more than these two causes for the stress on monarch populations.”

READ OUR PREVIOUS INTERVIEW WITH AGRAWAL

Agrawal said the new data and analyses from Monarch Watch “are valuable and contribute to our growing understanding” but cautioned against drawing the conclusion that herbicide and the lack of milkweed are the only cause of the monarchs’ woes.

“Like all studies, this new one has its limitations, some of which are acknowledged in the paper. For example, inferences are derived only from butterflies that die and are found in the Mexican forests while overwintering. It is easy to imagine that the subset of butterflies that die in Mexico have a very different story to tell than those that survive,” he said.

Threatened by extinction

In addition to the loss of milkweed to agriculture, Agrawal said that extreme weather, disease and habitat loss also play important roles in the steep and persistent decline in the number of monarchs that overwinter in Mexico. He has warned that one of the animal world’s greatest migrations, in which hundreds of millions of monarchs travel several thousand kilometers from their feeding grounds in the eastern US and Canada to their overwintering locations in the forested mountains of Mexico, may be lost forever.

In an April 2019 commentary published in the PNAS journal, Agrawal warned that the plight of the monarch is also symbolic of greater problems.

“Monarchs are sentinels, traversing the continent and tasting their way as they move. Thus, to understand what is happening to environmental health more generally, monarchs may be a source of information for both our own population and biodiversity writ large,” he wrote. “Monarchs are representatives of many species, and we should listen to what they are telling us.”

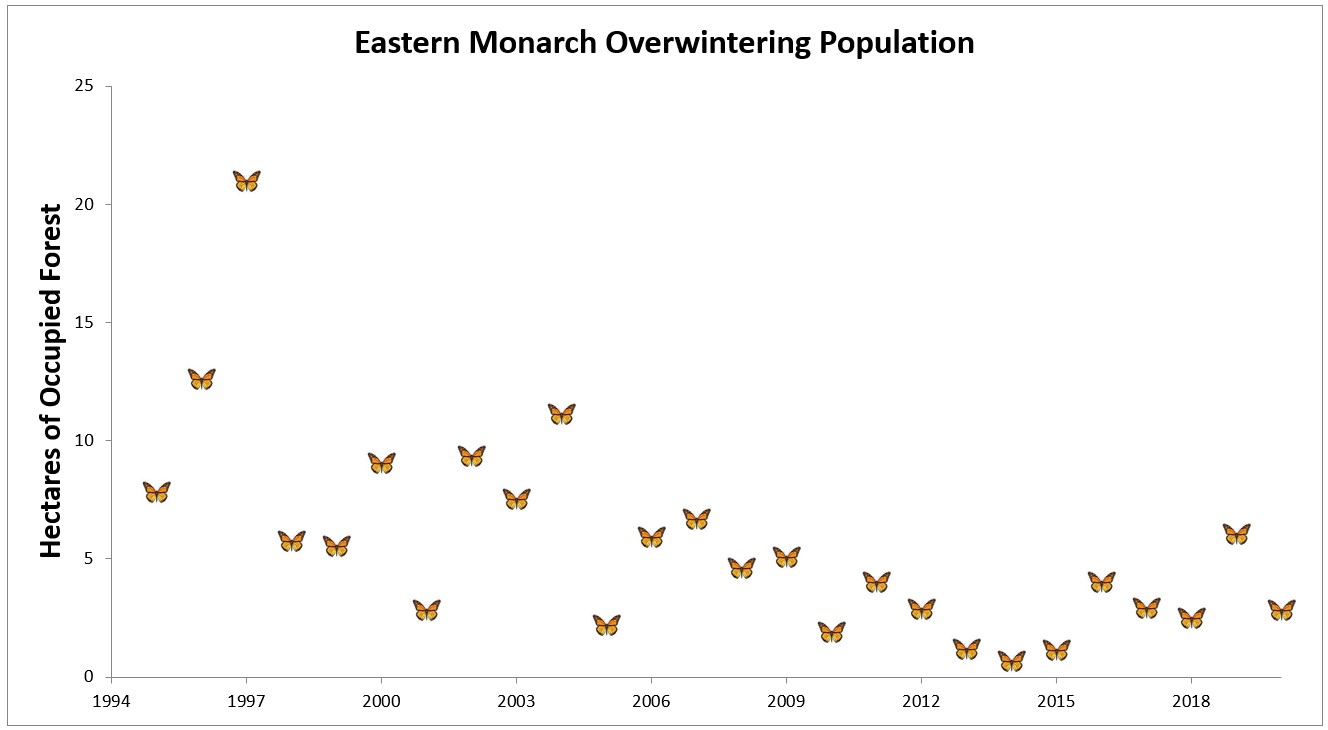

The monarch butterfly population in North America has dropped by as much as 90 percent over the last two decades. The World Wildlife Fund Mexico’s yearly count of monarchs released in March was 53 percent lower than last year’s count and that the butterflies occupied just 2.83 hectares, well below the six-hectare threshold that scientists have identified as necessary to stave off extinction.

Main image: Cathy Keifer/Shutterstock