With Nigeria’s recent approval of genetically modified (GM) cowpea, Prof. Mohammad Ishiyaku reached the end of what he termed a “10-year slow walk journey.”

“Ten years is a very big chunk of an individual’s lifetime,” said Ishiyaku with a smile as he leaned back in his chair at the Institute for Agricultural Research (IAR) in Zaria-Nigeria. “But 10 years working to improve the livelihood of a nation or community is a negligible part of my entire life, considering the economic benefits that will result from the adoption of this [GM] technology.”

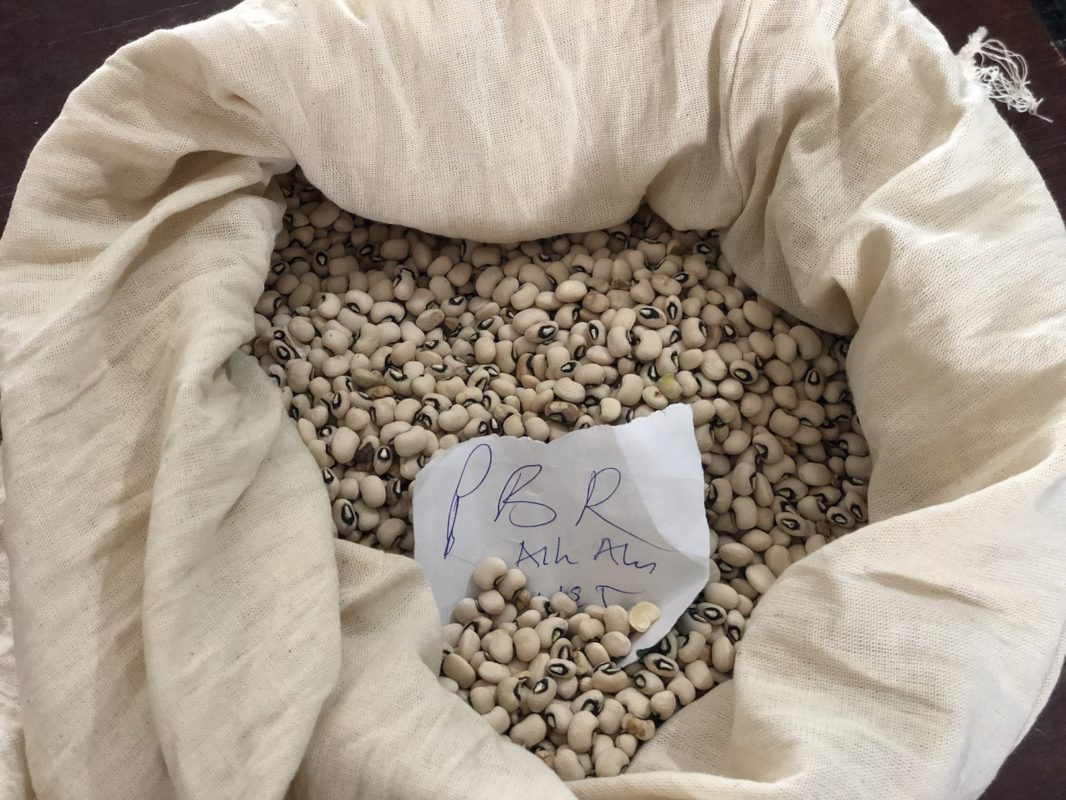

Ishiyaku, the principal investigator of the GM pod borer-resistant (PBR) cowpea, ticked off the benefits: a drastic reduction in the use of pesticides, increased crop yields and improved livelihoods for farmers in Nigeria.

“This is what kept me going,” said the plant breeder and geneticist, who has more than 30 years of experience working at the IAR.

Ishiyaku and other IAR scientists conducted a decade of intensive research and field trials to ensure the safety and effectiveness of the crop, which is also known as Bt cowpea in reference to the gene that confers resistance to the destructive pod borer pest. Their work finally met success last December when the government approved the commercial release of PBR cowpea — its first GM food crop. Pest-resistant Bt cotton was commercialized in mid-2018.

The landmark decision made Nigeria the first country in the world to take a biotechnology approach to repelling Maruca vitrata — the pest that can cause up to 80 percent yield loss in cowpea, an important source of protein in the diet of millions of Nigerians and other West Africans.

Ishiyaku had long observed that almost all Nigerians consume cowpea products such as akara — a popular meal made from peeled cowpea and consumed for breakfast in many parts of West Africa — and understood it was a nutritious and critically important staple food. He was also familiar with the constraints that limit cowpea production on the farm.

In response, Ishiyaku decided to focus his research on cowpea, using conventional breeding methods to develop new varieties resistant to insect pests. But several trials proved unsuccessful. It was 1998 when he first recognized that biotechnology could be the only way to solve the problem of insect pest attacks on cowpea.

“From my training as a plant breeder and geneticist, I had the practical and theoretical knowledge of how the genetic potential of [plant] organisms can be utilized to improve our food and by extension, transform human lives,” he explained. “Thus, in the case of cowpea, I thought the only alternative was to develop a GM cowpea that can protect itself against the pod-boring insect using genetic engineering.”

Genetic engineering has been used by scientists throughout the world to help combat food insecurity, treat diseases and improve the livelihoods of farmers. Nigeria joined that effort in 1992 when it signed the international Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). In subsequent years it ratified the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety (CPB), established the National Biotechnology Development Agency (NABDA) and created the National Biosafety Management Agency (NBMA) — all to guarantee public safety in the practice and application of biotechnology in Nigeria.

Ishiyaku welcomes those measures as evidence that the government supports the adoption of GM technology and recognizes the role of science and technology in advancing national development.

“In 2018, the president signed an executive order directing the deployment of science and technology for national development,” he recalled. “That alone is a very strong political commitment that opened the door for our work and science to flourish. Thus, there’s a policy-shift towards deploying science which has contributed to our success in developing the GM cowpea.”

Ishiyaku said the greatest obstacles that he faced came from a pocket of policymakers and others, including scientists, who do not fully understand the potential of GM technology, as well as the logistical challenges of his research work.

However, partners like the Nigeria chapter of the Open Forum on Agricultural Biotechnology in Africa (OFAB) aided his efforts by providing a platform for disseminating credible information and engaging the public in discussions about GM technology.

“This has greatly enhanced our capacity to surmount these challenges thus far,” Ishiyaku said.

Though approval was a long time in coming, Ishiyaku said he wasn’t surprised to learn the government had finally decided to allow farmers to access the Bt cowpea.

“The government was only reasonable enough to respond to the needs of its citizens through the deployment of science and technology, despite many fabricated stories against the use of genetic modification technology,” he said.

In addition to the personal satisfaction of seeing his own work come to fruition, Ishiyaku thinks that Nigeria’s approval of Bt cowpea will have ramifications elsewhere on the continent.

“The Nigerian scenario will most likely influence how the Ghanaians, and to a large extent West Africa, will deploy the GM technology,” he predicted. “Nigeria`s decision will lessen the resistance in Ghana and in other African countries who are already developing their own GM cowpea varieties.”