As the window for public feedback to the US Department of Agriculture’s proposal for labeling GMO foods closed on Tuesday, America’s farmers are at loggerheads with food industry giants over which ingredients should merit a “bioengineered” designation.

According to a report from Reuters, food companies including Nestle, Hershey and Unilever want the USDA to require manufacturers to label processed food products that contain ingredients from genetically-modified crops. Nestle, the world’s largest food maker, contends that ingredients such as canola, soybean oils and sugar should be labeled as bioengineered in the name of transparency.

“Consumers want to know what is in their food and beverages and we believe that they deserve transparency. It’s at the core of our business,” Nestle spokeswoman Kate Shaw told Reuters in a written statement.

A spokesman for rival Hershey made a similar argument, telling Reuters that labeling GM ingredients would help meet “consumer expectations on transparency”.

But farmer groups like the American Sugar Beets Association argue that their products are so refined by the time that they make it into processed foods that they no longer contain transformed genes and should thus be exempt from the labels.

“The law has been very clear that the required disclosure is going to be for those crops or ingredients that contain the genetic material,” Luther Markwart, head of the American Sugar Beets Association, told Reuters. “For things like sugar and other refined products that don’t contain the genetic material, the law does not apply to us.”

In an August 2017 letter submitted to the USDA, the United States Beet Sugar Industry, which represents 21 associations across 11 US states, urged the agency to exempt sugar produced from bioengineered beets from its labeling program.

“Sugar produced from sugar beets bioengineered to be resistant to the herbicide glyphosate is molecularly identical to sugar produced from conventional sugarbeets and from conventional and organic sugarcane,” the associations wrote, adding that there is “no legal or scientific basis” to differentiate beet sugar from other sugar products.

“It is a time to lead on the science and not acquiesce to unfounded fears,” they wrote.

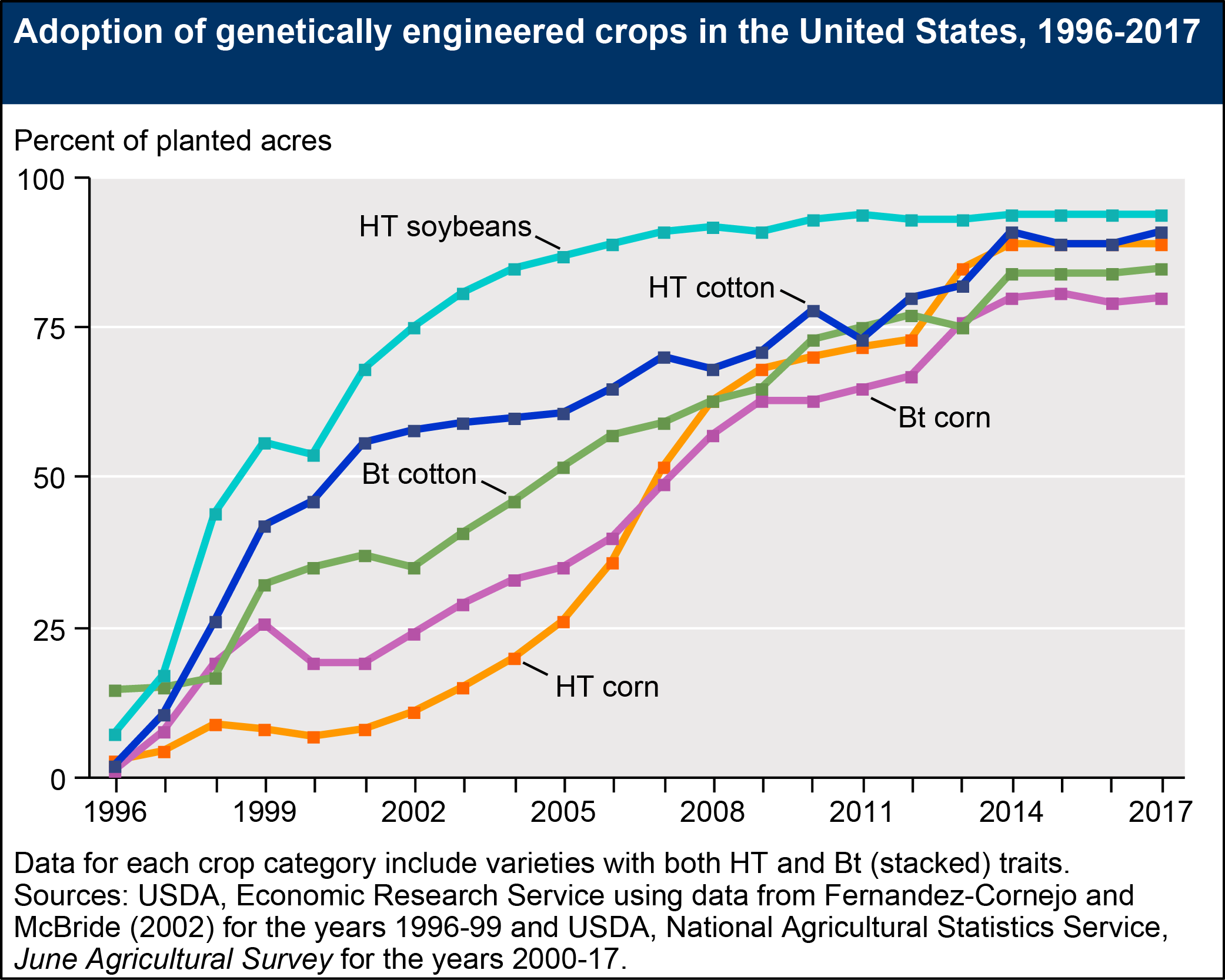

US sugar beet growers “have produced 100% bioengineered plants since 2015”, the groups added. According to the USDA, the vast majority of corn, soybean and cotton crops in the United States are also bioengineered.

Graph: USDA

Graph: USDA

Despite the widespread adoption of GE crops in the United States and a scientific consensus that those crops are as safe as conventional breeds perfectly safe, the food industry giants – and plenty of pro-GMO groups – argue that consumers have the right to know what is in their food products even if the GE crops have been so refined as to no longer contain transformed genetic material.

The Grocery Manufacturers Association on Tuesday released a statement urging the USDA to apply the federal labeling law to “refined ingredients derived from bioengineered crops in food and beverage products”. The group argued that with roughly 90 percent of the US corn, soybean and beet sugar crops being bioengineered, exempting refined ingredients from the coming label law “would result in 78 percent fewer products being disclosed under the federal law.”

The National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Law was signed into law by President Barack Obama in July 2016. With the window for public feedback now closed, the USDA is required to finalize the rule by July 29. Large companies will have to comply by Jan. 1, 2020, while smaller food manufacturers will be given an additional year. However, companies can use up their existing inventories of food labels through Jan. 1, 2022.

The food companies will have three options for disclosing the presence of bioengineered (BE) ingredients: written text, a symbol and scannable QR codes. The proposed “BE” symbols range from smiley faces to a bucolic representation of blue skies, bright sun and green land.

In the end, the farmer groups concerned about a GMO backlash may find that their worries were for naught. According to a study published last month, consumer opposition to GMO foods in Vermont, the only US state to have implemented its own mandatory labeling law, fell by 19 percent after the state law took effect in July 2016.

“What seemed to matter most to people was simply that the labels were there,” David Ropeik, an author and expert on the psychology of risk perception, told the Alliance for Science. “The study suggests that just by being there labels are more likely to reassure and encourage acceptance of GMOs than scare them away.”

Photo of a Michigan sugar beet farm: Christopher Collins/Flickr