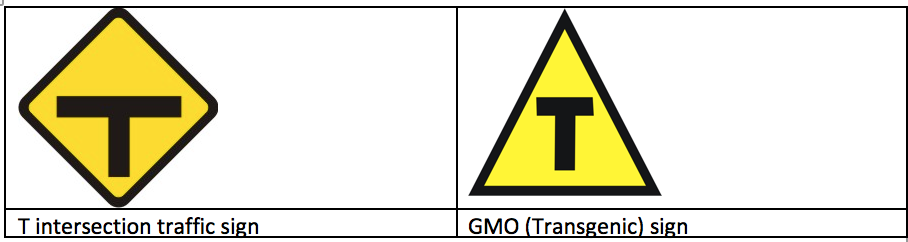

What is the difference between these two signs? Both show a black T inside a yellow warning shape.

But in Brazil they have very different functions. One is a genuine warning, as a road sign warning of an upcoming T intersection. The other indicates the presence of transgenic material in a food product, which scientists around the world agree is as safe as any other food.

But in Brazil they have very different functions. One is a genuine warning, as a road sign warning of an upcoming T intersection. The other indicates the presence of transgenic material in a food product, which scientists around the world agree is as safe as any other food.

Activists in Brazil are up in arms at a proposal currently being considered in the Brazilian Senate to remove the black and yellow T on food containing transgenic material. There have been howls of protest about the supposed secrecy of food companies, and predictable misinformation circulated by campaigners about the supposed health dangers of GMOs (there aren’t any).

However, the campaigners are barking up the wrong tree. Although the proposed legislation does eliminate the scary warning T label, it replaces this with text in the food product’s ingredients list advising of the presence of GMOs when detectable levels are over 1 percent. This is hardly the “secrecy” anti-GMO activists are decrying – indeed, the proposal even allows for a “GM-free” label where the total absence of transgenic material can be proven.

Consumers’ right to choose what they eat is crucial, but information on labels should be helpful and not misleading. Labels should give consumers information to make informed choices. But the existing T label contradicts the fact that all commercially available GMOs are subjected to rigorous risk assessments on a case-by-case basis — evaluations that conventional foods are not required to pass — and that scientific research has been conducted over decades without ever demonstrating a single instance of damage to human health or the environment.

The current T sign sends an exaggerated and distorted image of modern science and agriculture, denying its successes and social repercussions, and discouraging purchase through promoting fear. It does not make our food safer or enable healthier choices. Similar labels do not exist for certain foods that can genuinely cause food allergies and intolerances, such as gluten, lactose, peanuts or sugar. So why stamp a warning sign on a safe product/ingredient and not on those that can cause scientifically-provable health problems in certain people?

At first glance, labeling properly might seem simple but actually it is very complex. There is no international consensus on how GMOs should be labelled. In some countries, GMOs are not labeled because they are considered equivalent to conventional food and safe for consumption. In others, labeling is voluntary, or in some cases must follow strict rules.

While some countries have adopted a label for GMOs, Brazil is the only country in the world that stamps a symbol that raises the false perception of danger. An international scientific consensus exists that genetically modified foods are safe for human consumption.

When GMO and non-GMO foods are virtually identical, labeling can be deceiving. Most of the cheese in the world is made with the help of enzymes produced by genetically modified microorganisms, but the end product is not considered a GMO. This is also true for beer and wine. If you feed an animal with transgenic material, the animal will not itself become a GMO. In countries where GMOs are labeled, you can find a range of traces allowed before a product is labeled as a GMO. In the European Union labelling is above 0.9 percent (not yet properly implemented) and in Japan, it’s 5 percent

What many people do not know is that the lower the acceptable trace, the more complex the implementation and the higher the costs. At the end, the food product will be more expensive for the consumer, worsening social inequality as poorer people tend to spend a higher proportion of their household budgets on food. In addition trying to label something that is not detectable encourages fraud. Setting acceptable trace levels is important to implement the legislation, enable inspection and for enforcement. The proposed new requirement in Brazil is of detectable 1 percent ingredient in the final product.

Brazil is the second largest producer of GMOs in the world. The 14-year-old fearmongering GMO sign, so commonly stamped on products made in Brazil, has actually failed to inform consumers. According to a 2014 survey by Ipsos and Associação Brasileira das Indústrias de Alimentos (ABIA), only 6 percent of the 1,000 respondents even know the meaning of the current GMO sign. A text stating the presence of GMOs is surely more transparent and easier to understand.

However, people are being asked to oppose the project on public consultation based on the misleading information that the GMO label in Brazil will completely disappear. It is important that when people vote on the public consultation they are not deceived by incorrect claims. Currently, the public “no” votes hugely outnumber the “yes” votes, perhaps because people are misinformed about the proposal.

Misinformation corrodes democracy because people are asked to make a decision based on deceptive claims. It is important that Brazilians understand that the proposal is not to eliminate labeling altogether, but to change from a label that most people do not understand to a more useful text in the ingredient list. If the substance of the proposal was better known, most consumers might agree that it is a step forward, not a step back.