The European Union and Australia took steps this week toward easing the regulatory process around certain genetic engineering techniques.

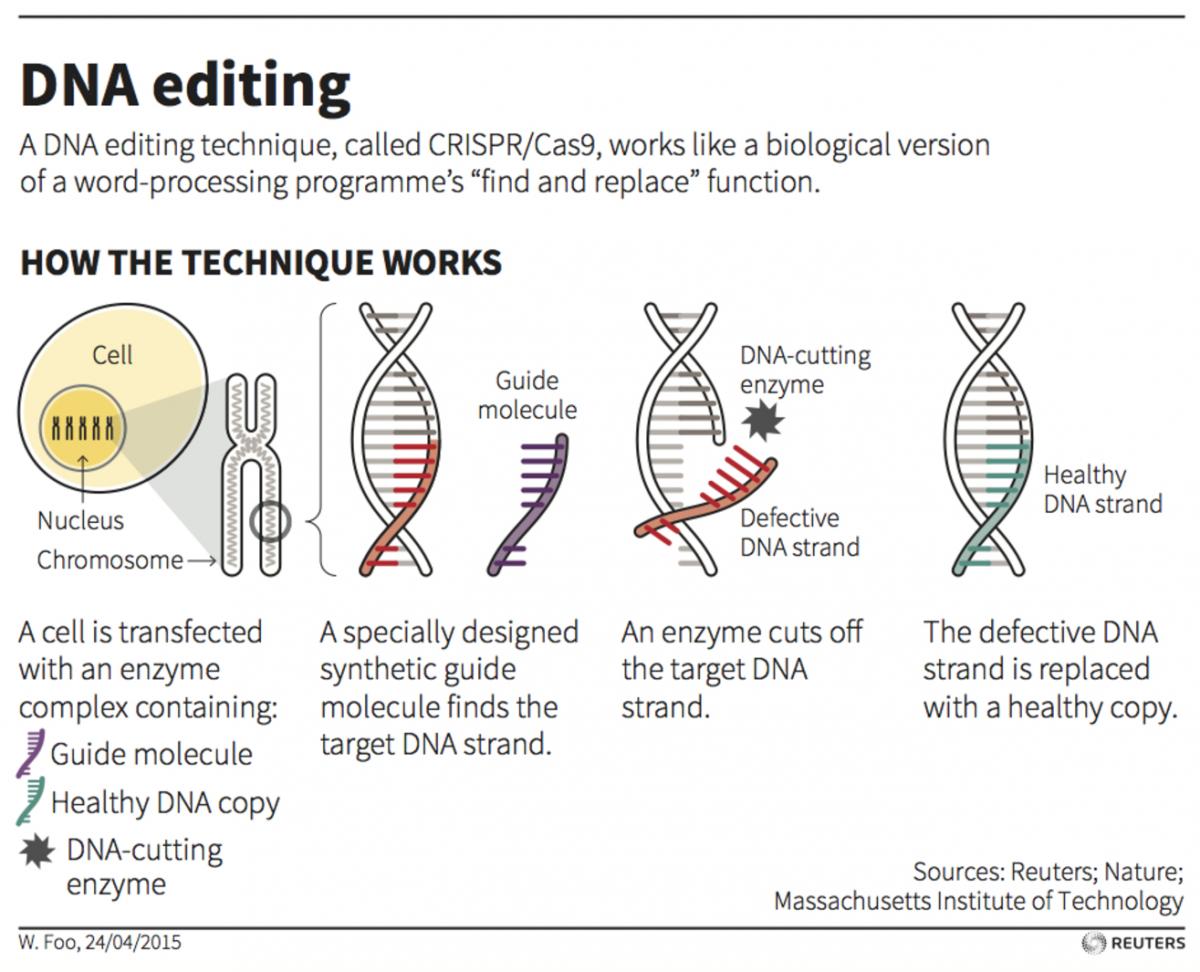

In the EU, a legal opinion found that mutagenesis techniques are, in principle, exempt from the rules that govern genetically modified organisms (GMOs), though individual EU states can regulate their use. Meanwhile, regulators in Australia recommended reducing regulations around CRISPR and other new gene editing processes.

Neither mutagenesis nor gene editing typically entail the insertion of foreign DNA into a living organism, a highly regulated process known as transgenesis.

As Australia’s gene technology regulator Raj Bhula explained in an interview with ABC Australia:

With gene editing you don’t always have to use genetic material from another organism, it is just editing the [existing] material within the organism. All of our regulatory frameworks and laws have been established based on people putting unrelated genetic material into another organism.

Whereas this process is just manipulation within the organism and not introducing anything foreign.

It s an argument that researchers, and increasingly regulators, have been making around the globe to press for GMO regulatory revisions that take into account new advances in the fields of biotechnology and synthetic biology.

As Bhula reasoned:

“If these technologies lead to outcomes no different to the processes people have been using for thousands of years, then there is no need to regulate them, because of their safe history of use. If there is no risk case to be made when using these new technologies, in terms of impact on human health and safety for the environment, then there is a case for deregulation.”

A similar rationale can be found in the opinion that EU Advocate General Michal Bobek released yesterday in response to a legal challenge by a French agricultural union to the EU s mutagenesis exemption:

The Advocate General points out that neither the historical context nor the internal logic of the GMO Directive support the contention that the EU legislature only intended to exempt safe mutagenesis techniques as they stood back in 2001. He considers that a generic category labeled mutagenesis should logically encompass all those techniques that are, at the given moment relevant for the case in question, understood as forming part of that category, including any new ones.

The Advocate General does not see any grounds deriving from the general duty to update legislation (in this case enhanced by the precautionary principle) which could affect the validity of the mutagenesis exemption.

Bobek s opinions are not binding. However, they are usually followed by the European Court of Justice, which is expected to rule on the case in the next few months.

In Australia, Bhula s recommendations are now open for public review, and will require approval by Commonwealth and state and territory governments, as well as federal Parliament.

Though the National Association for Sustainable Agriculture Australia, which represents organic farmers, has opposed the recommendation, plant researchers say gene editing will allow them to quickly and safely breed new climate tolerant crops.

As Caitlyn Byrt from ARC Centre of Excellence in Plant Energy Biology at the Waite Research Institute, University of Adelaide, in South Australia, told Cosmos magazine:

The food our children eat in the future will have a different DNA sequence to the food we eat today. We are on a trajectory for increases in drought frequency which will result in a decline in crop productivity. To protect future food security we require crop varieties that can maintain productivity in a climate with limited rainfall and higher temperatures. The development of crop varieties with improved performance in hot and dry conditions can only be achieved by modifying the genome.

In any case, Bhula expects no opposition from consumers. As she told ABC Australia:

We have conducted a community awareness survey and what we found is some of the opponents were more worried about not having choice when buying GM products.

Australia s 12-month technical review of current regulations also considered the use of gene editing in humans, which is riskier because of genetic differences between patients. As Bhula noted:

“When you are looking for a very specific outcome with human health, it’s good to proceed with caution, but with plants you can see the outcomes or breed out the effects you don’t want in the final product. That’s not so easy to do that with humans.”