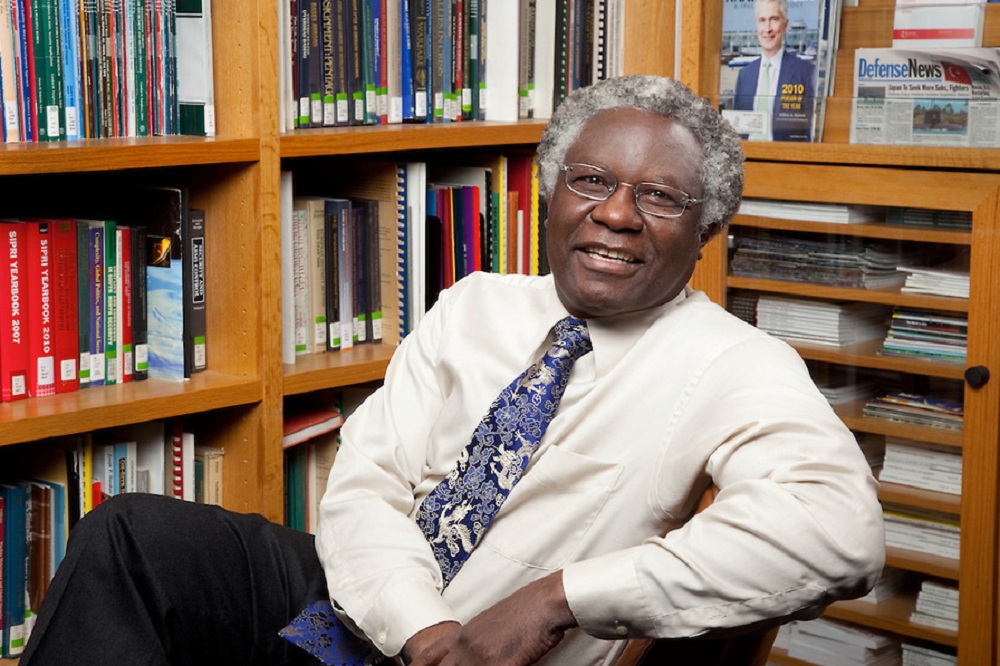

Professor Calestous Juma: June 9, 1953 – Dec. 15, 2017

To outsiders, Calestous Juma’s rise from humble origins in a remote Kenyan village to an internationally recognized Harvard scholar, science writer and public intellectual, might have seemed improbable. But as Juma himself liked to tell the story, he learned innovation from his parents, whose poverty meant that they constantly had to change to survive.

Life for the young Calestous was not easy. Born on June 9, 1953, in Port Victoria, close to the Ugandan border in the far west of Kenya on the shores of Lake Victoria, Juma as a boy suffered repeated bouts of malaria, a frequent killer then as now of young children in the region. When he was just nine years old, floods inundated his village, leading to food shortages for the whole community.

The floods gave Juma his first experience of innovation, however. His father, John Juma, a carpenter, travelled to neighboring Uganda and returned with cuttings of cassava a starchy, resilient tuber that is a staple elsewhere in East Africa, but was at the time unknown in that part of Kenya. The elder Juma proposed that the flood-stricken villagers replant with dependable cassava.

Like many innovations, John Juma’s introduction of cassava was hotly debated in the village. When wild pigs, displaced by the floods, further damaged the village’s remaining crops, some blamed cassava for attracting them. “They were worried these plants would breed demons,” his son recalled later. His father eventually won the argument, however, and cassava has since become a nationwide staple.

The episode inculcated Juma with a lifelong interest in technology innovation, the environment and agriculture. This would later be parlayed into worldwide influence as the Executive Secretary of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) between 1995 and 1998, as author of several books on innovation and farming, and most recently as Professor of the Practice of International Development at the Harvard Kennedy School, from 2002 until his death last Friday after a two-year battle with cancer.

Juma’s early life also brought out his entrepreneurial spirit. Always a technology enthusiast, he began fixing broken radios and record players at the age of 12, and was excused from church on Sundays to develop his small business. The enterprise helped Juma meet his own school fees. “I had a job first, then retired into school,” he would joke in later years.

Juma’s mother, who gave up farming to pursue a more profitable career as a trader of fish, maize and other foods, was also an inspiration. She learned a second language, Luo, to help her develop the business. “Being able to think about new things, doing new things, experimenting, was always a big part of my early childhood,” Juma remembered.

But money remained a problem. With his family unable to afford the cost of further education, Juma worked as a science elementary school teacher in faraway Mombasa, on Kenya’s east coast. Classes ended at midday, and in the afternoons Juma sometimes penned letters on various issues to the Daily Nation newspaper. His engaging and witty writing style made him popular, and in 1978 the Daily Nation hired him as sub-Saharan Africa’s first dedicated science and environment journalist.

After six years abroad at Sussex University in England, there gaining a PhD in science policy, Juma returned to Nairobi in 1988 to found the African Centre for Technology Studies, the first organization of its kind on the continent. He spearheaded the new institute until moving to Montreal, Canada, in 1996 as head of the UN s CBD. He was never to return to live in Kenya.

In 1998, Juma left the UN for Harvard, partly because as he stated he could not bear to see the Cartagena Protocol passed on his watch as CBD executive director. The Protocol ushered in an extremely restrictive approach to biotechnology in Africa, leading to prohibitive policies that kept GM crops locked out of the continent with precious little scientific justification. Remembering, perhaps, his father’s experience with cassava adoption, Juma called Cartagena the product of a “pessimistic world view.”

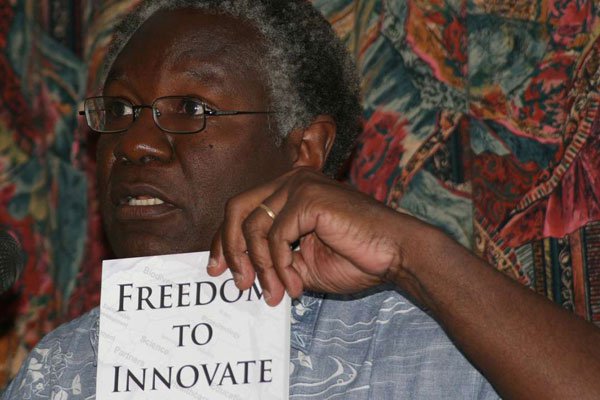

For speaking out in defense of agricultural innovation, and in particular on the controversial issue of genetically modified crops, Juma found himself vilified by anti-GMO activists. However, he refused to hit back, gently reminding critics that he was no single-issue advocate. His 1989 book The Gene Hunters was indeed one of the earliest warnings that the biotechnology revolution could be a double-edged sword for Africa.

Moreover, Juma was careful to point out GM crops would only work as part of a broader project to improve agriculture in the continent. “There is no use replacing your computer s processor if you don t have electricity,” he commented. Nevertheless, the relentless opposition of many people to technological novelty fascinated him. His final book, Innovation and its Enemies, chronicled new technologies and their opposition, from the printing press to margarine to refrigeration.

Even toward the end of his life, in failing health and having lost his famous shock of grey hair after months of cancer treatment, Juma lost none of his irrepressible good humor. He charmed the audience at The Breakthrough Institute conference in June 2017, where he was awarded The Breakthrough Prize. In a spirit of typical generosity, he immediately donated the prize monies back to the Institute for its young fellows training program.

More, perhaps, even than for his intellect and charm, Calestous Juma will be remembered for his optimism. Ultimately, all development is experimental. No one knows what they are doing, he told one journalist in a 2014 interview with a chuckle. Africans need the chance to experiment as well. They will make mistakes, but they can learn from them too.

Calestous Juma is survived by his wife, Alison, and son, Eric.