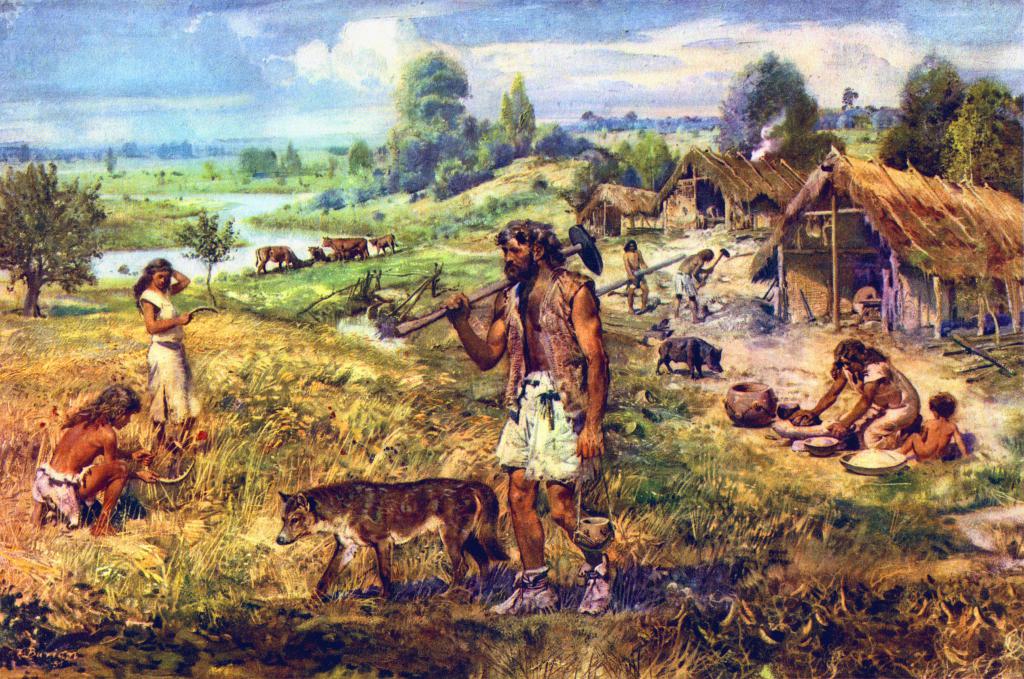

Imagine that we decided to abolish farming across the world. The cities emptied, the combines sat idle, and all 7.5 billion of us scattered out into the countryside in search of nuts, berries, and game to make our livings as modern-day hunter-gatherers. How would that go?

The answer is not well. Ecologically speaking, there could be no quicker and more effective way to eliminate most of life on Earth. It takes roughly 6 square miles to support one hunting-gathering human. Modern intensive farming, by contrast, can support up to 4,000 people on the same land area. That means we would need another 12 planets to support today s human population in an entirely hunter-gatherer system.

This is, of course, only a thought experiment. Without technology and ingenuity to extract more food from smaller areas, the population would never have reached today s levels.

This doesn t mean all is rosy. Hundreds of millions of people, primarily in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, remain in low-input, low-yield subsistence agriculture. In North America, Europe and other developed regions, modern agriculture is hugely efficient in land and labor terms.

Modern farming has also become politically controversial. The organic movement has challenged the whole model of industrialized farming, seeking to move to a less intensive ideal that proponents feel is closer to nature. Debates rage about pesticides, hormones, animal welfare, and so on. Trade-offs are rarely acknowledged. For example, organic s lower yields inevitably mean that more land must be tilled up to feed the same number of people, so the net environmental effect may be negative.

Ecomodernism, a more progressive variant of environmental thinking, seeks to take a pragmatic approach to these challenges, welcoming technology where this can make humans less dependent on nature. As a group of environmental activists and thinkers (of which I was one) wrote in the Ecomodernist Manifesto in 2015:

Ecosystems around the world are threatened today because people over-rely on them: People who depend on firewood and charcoal for fuel cut down and degrade forests; people who eat bush meat for food hunt mammal species to local extinction modern technologies, by using natural ecosystem flows and services more efficiently, offer a real chance of reducing the totality of human impacts on the biosphere.

The math is simple. Supporting a growing population without increasing farmland requires increasing crop yields. Yield gaps in poorer countries need to be closed with better crop genetics and modern ag techniques.

Farming is often demonized as selfish and destructive of the planet. Yet, we need farmers especially enlightened farmers more than ever.

Farmers need to be allowed to innovate and adapt. One example of the debate around GMOs shows what happens when this goes wrong. Europe is now the dark continent when it comes to modern molecular crop breeding. Like the medieval fear of witchcraft, popular suspicion of scientists tinkering with genes has held back progress for a quarter of a century. That means European farming is less productive and more chemical-dependent than it would otherwise be. Hardly a good outcome for the planet.

Ecomodernists want to see science fully applied in agriculture so that farmers can do their job of growing food in the most sustainable and productive way they can. There is nothing progressive about trying to block progress. If you re a farmer who wants to make the best of your land both for yourself and for future generations, and if you believe the future can be better than the past, you are probably an ecomodernist, too.

Mark Lynas is a Visiting Fellow at the Alliance for Science. This piece originally appeared in Modern Agriculture.