In Africa, a child is said to be raised by the whole community.

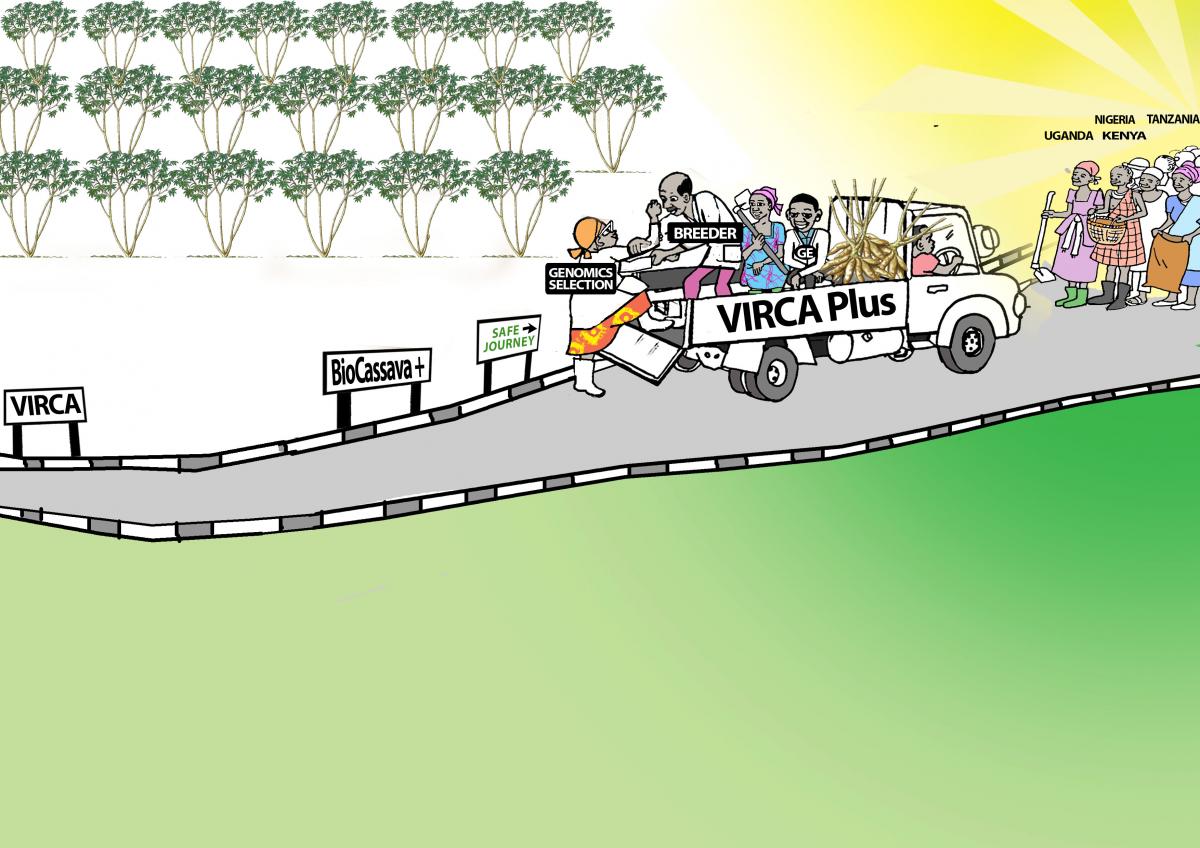

The VIRCA Plus project is taking a similar approach relying upon a community of scientists, policy-makers and farmers to develop a farmer-preferred cassava variety resistant to the deadly cassava mosaic and brown streak viruses.

Cassava is a big staple consumed across Africa and is regarded as one of the most important food security crops capable of surviving through drought. This crop has been vulnerable to viruses over the years. The first virus that affected the entire African continent was cassava mosaic virus, which caused serious crop losses in many countries, including Uganda, where it almost became a national crisis. Committed responses from cassava breeders resulted in several resistant varieties being developed for farmers.

But cassava scientists had no time to rest before another virus struck the one that causes cassava brown streak disease. This tuber-spoiling virus caused up to 100 percent loss in some areas. Varieties tolerant to this disease were eventually developed, but the tolerance breaks down after few cropping cycles. Farmers grew tired of receiving new crops so frequently, and were unable to adjust to the differences in taste. To scientists, it wasn t about taste, but stopping the disease and ensuring households remained food secure.

Now the VIRCA Virus Resistant Cassava for Africa project is using genetic engineering to fight disease and develop a variety that farmers prefer. The project succeeded in introducing, for the first time, total resistance to cassava brown streak virus into a farmer preferred variety called TME 204. This milestone opened up VIRCA to new opportunities that had previously not been envisioned, such as using the conventional breeding approach to confer virus resistance into farmer-preferred varieties that are resistant to mosaic, but susceptible to the brown streak virus. Conventional breeders, with all their uniqueness and expertise, were brought on board, and plant crossings were made in both Kenya and Uganda, producing thousands of seeds resulting in thousands of new potential varieties. But how could these thousands of materials be reduced to a virus resistant variety for farmers? Traditionally scientists took these materials and planted them in screen houses, where they were subjected to the conditions they were bred to resist. Those that survived were carried forward for more evaluations a process that could take over 10 years, and still deliver a product that didn t fully please farmers.

Scientists thrive on challenges

Instead, scientists are using a modern biotechnology tool known as genomics selection to skirt the process of having to screen thousands of plants. Scientists with the Cornell University-based NextGen Cassava project have genome-based selection tools that are able to identify seedlings with the potential to resist both viruses in addition to those that can give good yield. This process more than halves the burden and drudgery associated with traditional, less-precise breeding methods. Recently scientists from IITA also published findings that would facilitate genomic selection of farmer preferred traits (characteristics) before proceeding to field trait selection trials. They identified the genetic markers associated with resistance to cassava brown streak disease and cassava mosaic disease after studying two local varieties grown in the disease hotspot areas of Tanzania.

From its inception, the VIRCA Plus project involved farmers in its field trials and also explained the processes of genetic engineering and why it was chosen as one of the tools in developing new cassava varieties. Sarah Kirya is a member and a treasurer of the Kinyomozi Agateirani farmers group, and one of several farmers who have been involved in the VIRCA Plus project. In a local dialect, agateiranai means united, and Sarah and members of her group have united to fight household poverty. They grow maize, cassava and beans, and they also have tree plantations, selling the mature trees for poles and timber.

Sarah comes from one of the leading cassava growing regions in Uganda, which was not spared the devastating cassava brown streak disease. Farmers there prefer the nyaroboke variety because of its sweetness and the quality of its flour, which results in bread well accepted by local taste buds. Women normally make bread, which implies women should play a key role in selecting the variety that gets released to the communities.

Uganda s cassava program, conducted under the National Crops Resource Research Institute based in Namulonge, released two conventionally-bred varieties to Sarah s community: NASE (Namulonge Select) 13 and NASE 14. According to Sarah, these two varieties especially NASE 13 are high yielding, drought tolerant, disease tolerant and early maturing.

This raises the question of why farmers would need a resistant transgenic variety when they already have conventionally bred varieties. Sarah explained that in the past, farmers would typically mix different cassava varieties within one field. Currently, however, they are not allowed to grow the disease-tolerant variety alongside, or even near, any disease-susceptible varieties. If farmers fail to adhere to this procedure, their planting materials would not be certified by the local authorities for sale. Farmers who choose to mix their tolerant varieties with the local ones end up having diseased fields due to the break down of tolerance. Sarah and her group said they need a variety that remains resistant even when grown near disease-susceptible varieties.

Despite the requirement of isolation, farmers still continue to grow their preferred variety, nyarobok,e which is susceptible to diseases. Nyaroboke is the market s darling and fetches a higher price. A bag of Nyaroboke cost $5 more than the conventionally improved tolerant variety. Though anti-GMO activists have claimed that GM crops will wipe away traditional varieties, it s clear that farmers will still grow local varieties alongside new varieties to supply different market demands.

Sarah also observed that the new varieties were initially difficult to mingle into bread because they never hardened to the point where the tubers could be ground into flour. However, to the amazement of farmers, by the third cropping cycle the new variety started behaving well, interacting with the environment and adjusting accordingly.

The introduced variety also produces a lot more, yielding 18 to 20 roots per plant compared to eight to 12 roots in traditional farmer preferred varieties. This also brings out the fact that the market is complex and should not be taken in a simplistic manner. Different commodities have different advantages that keep them in the market.

Now it seems that both farmers and plant scientists will be satisfied, thanks to the inclusive and participatory approach taken by VIRCA and VIRCA Plus. By bringing together expert scientists from genetic engineering and conventional breeding, using the tools of genomic selection, and involving farmers across Africa, the program is poised to deliver cassava varieties that offer desired traits, such as disease- and drought-tolerance and high yield, while still meeting the cultivation and taste requirements of regional farmers.

Isaac Ongu is a Uganda-based journalist who specializes in agriculture.