Public sector scientists from around the world are descending on Cancun, Mexico, this week in preparation for a fortnight-long battle to defend the frontiers of biotech research, which are at risk of being closed off by anti-science NGOs fiercely lobbying national delegates at the upcoming meeting of the UN’s Convention on Biodiversity.

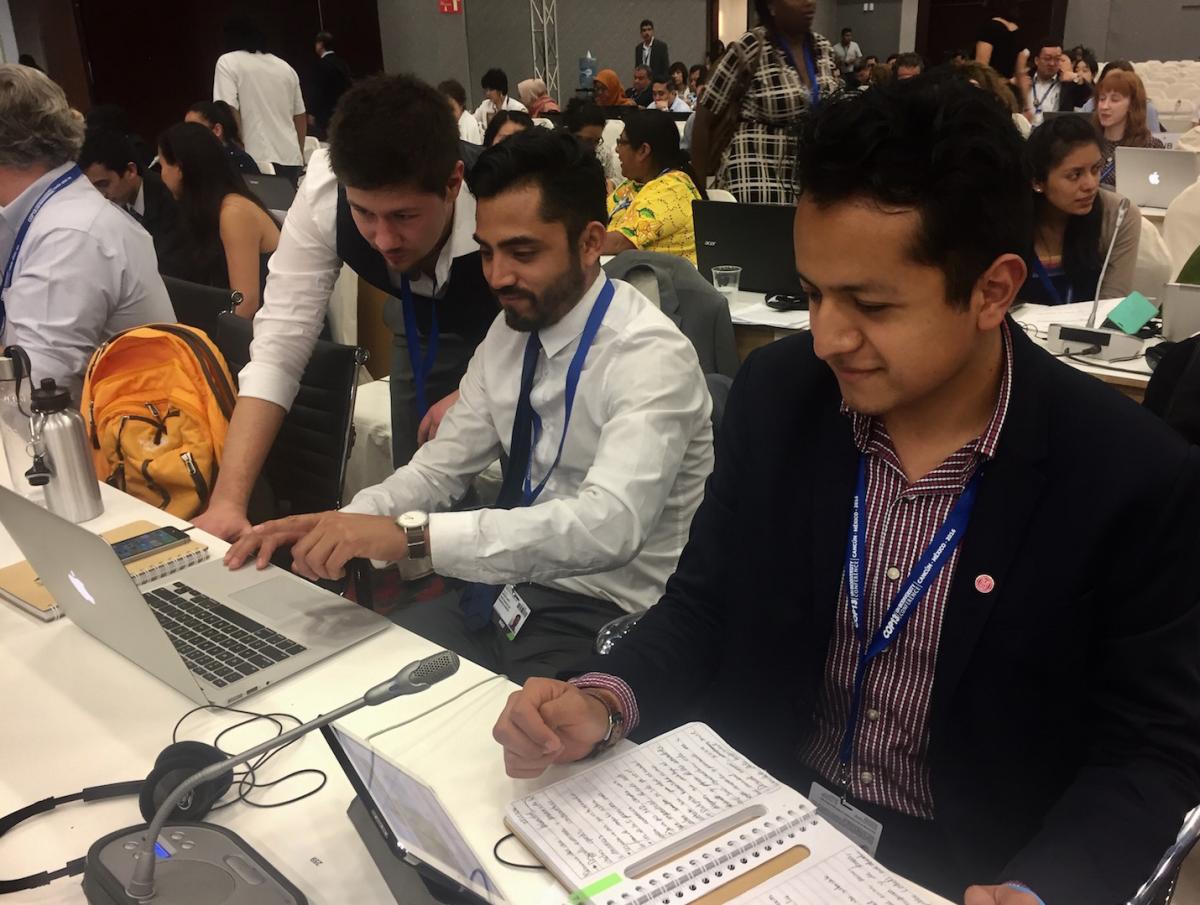

Fellows from the Cornell Alliance for Science and young biotechnology students will be joined in Cancun by representatives of PRRI the Public Research and Regulation Initiative, a worldwide coalition of public sector scientists involved in pursuing modern biotechnology for the public good. Hundreds of scientists, many representing developing countries, are part of the overall PRRI network and will contribute their expertise.

The UN Biodiversity Conference is taking place from Dec. 4-17. While most of the meeting is intended to address the serious challenges of declining wildlife populations and species loss worldwide, synthetic biology is also on the agenda. Scientists are keen to learn from the experience of the Cartagena Protocol, which was intended to fairly address LMOs that may have adverse effects effect on biodiversity, as well as recognizing the great potential of modern biotechnology for human well-being, when it was agreed upon in 2000, but ended up seriously hampering the use of genetic engineering, particularly in developing countries.

Activist groups and well-resourced international NGOs can have a significant influence on the outcome of UN environmental negotiations, which are extremely complex and can place a huge burden on time-limited delegates, especially those with few resources from Africa and other developing regions. NGOs produce large quantities of information and host side events often aiming to restrict scientific progress on biotech and hamper the use of genetic technologies in poorer countries.

For example, the anti-capitalist Third World Network produces a Biosafety Information Service typically focusing exclusively on the risks of GMOs, and ignoring any benefits. One side event hosted by the anti-GMO network ENSSER (which insists there is no scientific consensus on GMO safety, despite all accumulated statements from major scientific bodies that GMOs are not riskier than conventional methods of genetic modification) will criticize the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation as an agent of “philanthrocapitalism” and oppose the distribution of drought-tolerant seeds to poorer farmers under projects like the Water Efficient Maize for Africa initiative.

In contrast, the scientific community typically struggles to make its voice heard. Scientists tend to shy away from overtly political meetings and are less apt to make the kinds of sweeping statements and loud appeals that can make NGO campaigners so effective. PRRI will aim to address this information deficit by reminding delegates of the importance of supporting science-based regulation that acknowledges both the likely risks and benefits of new technologies in a more balanced way.

Anti-science groups, for example, are aiming to include a highly restrictive definition of synthetic biology in the meeting’s outcome text in order to subject new and more targeted gene editing technologies such as Crispr to the same kind of non science-based regulatory regime as has seriously held back conventional genetic engineering in agriculture.

Particularly in the firing line is the emerging issue of gene drives, which anti-GMO activists have characterised as “extinction technologies” and demanded be banned. One anti-technology NGO called the ETC Group has published a statement claiming “gene drives pose wide ecological and societal threats and should be placed under a moratorium.”

Although there is widespread agreement among scientists that gene drives need to be handled with extreme caution and subjected to extensive testing before any planned releases, a permanent ban would foreclose the option of using this technology to wipe out major diseases such as malaria, potentially losing the opportunity to save millions of human lives. Ironically, gene drives can potentially also be used to save some wild live that are threaten to extinction due to invasive species.

In order to try to avert the threat of a UN-mandated moratorium, leading world scientists from the fields of medicine, public health, genetics and ecology have together signed an open letter urging delegates “to resist current advocacy efforts demanding a ban on gene drive research or on the future use of gene drive-based products.”

The letter states: “Imposing a moratorium on such promising life-saving and life-improving innovations so early in their development would be unwarranted, damaging and irresponsible. Blanket bans discourage research and prevent regulators, policy-makers and other stakeholders from having an informed conversation about the use of new technologies.”

It notes, as did a recent National Academies of Science report, that a potential application of gene drive technology is to reduce the burden of mosquito-borne diseases such as Zika, dengue and malaria, which together kill more than 1 million people every year. The costs of these diseases totals more than $12 billion in Africa alone.

In opposing NGO calls for a moratorium, the scientist signatories to the letter insist that gene drives should be considered rigorously on a case by case basis, just as are other new classes of medicines and vaccines. “A moratorium on the use of gene drive violates the case by case approach of these systems and risks closing the door on critical new tools,” they point out.

Ironically, given the UN meeting’s overall theme of protecting biodiversity, banning gene drives would also eliminate potential uses that the technology might have in avoiding the extinction of threatened species. One possibility is that the mosquitoes carrying avian malaria, which is wiping out native Hawaiian birds, could be targeted. Another idea, put forward by the charity Island Conservation, is the elimination of invasive mice from islands where they are wiping out endemic species.

“It is frustrating that efforts to solve real environmental problems and human suffering are threaten to be banned. Even when the possible risks are not an issue when used in a responsible way and taking some safety measures, or even before knowing whether all the proposed risks are actually real,” said Dr. Lucia de Souza, executive secretary of PRRI and a Visiting Fellow at Cornell University’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. “Think about electricity, there are real risks but we use it daily, because we learned how to do it safely. Doing nothing is not an option when we have real and growing issues on human, animal and environment health.”

Dr. Sarah Evanega, director of the Cornell Alliance for Science, commented: Now more than ever, organizations that care about the future of our planet must come together to make rational, evidence-based decisions about the utility of the tools we may need to address the environmental challenges we face today.