Reprinted from Farmers & Friends | March, 2015 www.farmersandfriends.org

In recent days, with little fanfare or attention from the press, a lot of people from New York and Hawai i rallied to counter a spurious attack against the integrity of biotechnology research specifically, and science generally. Two institutions figured prominently in this action Cornell University in Ithaca, New York and the University of Hawai i. Here s what happened.

In February, a new nonprofit group called U.S. Right to Know (USRTK) filed requests under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) to obtain three years worth of e-mail correspondence from 14 senior scientists at four U.S. universities. USRTK s request was a bid to demonstrate collusion among land-grant university scientists and the biotech industry.

At Cornell, the newly founded Alliance for Science (AFS), a program funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, mounted a defense. AFS saw the email request as a fishing expedition and smear campaign intended to malign the integrity of college scientists. The Alliance quickly launched a petition drive in defense of the Science 14.

Broad anti-science campaigns like this are hurting our society, said AFS. At a time when the world’s population is expected to rise to more than 9.5 billion by 2050, we need more science, not less, if we are to feed the world without destroying fragile ecosystems and driving more species to extinction.

AFS asked readers to join the fight for academic freedom and sign its letter in support of scientists under attack. The letter urged the Science 14 to stand strong in the face of anti-science bullying.

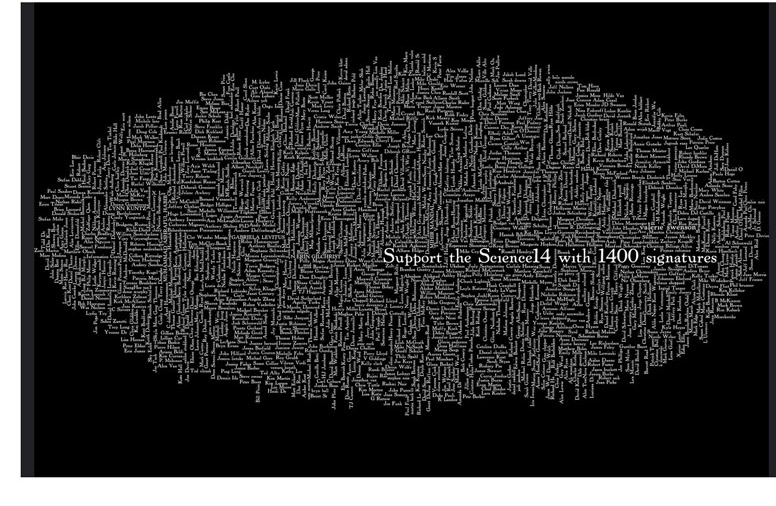

AFS set an initial target of 500 signers to its petition (seen here). That target was met within a day. A second target was declared 1,000 signatures in all. Within another 48 hours, 500 more signatures appeared. It was fast becoming clear that the Alliance for Science petition had struck a chord with people fed up with anti-science populism.

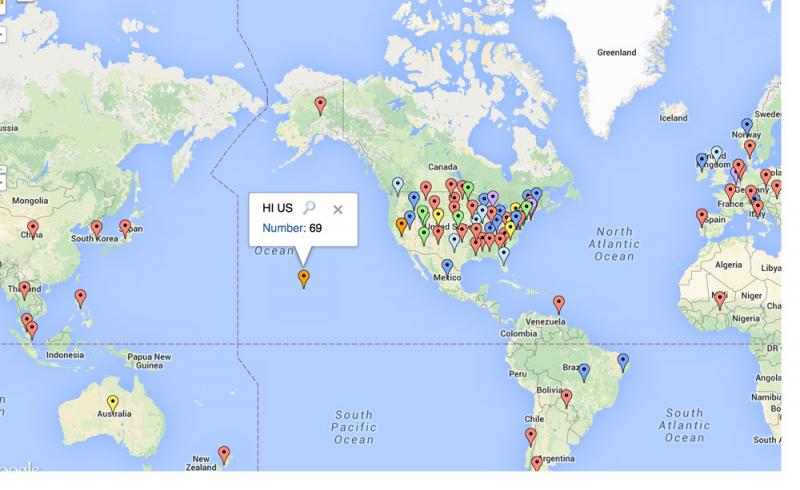

I watched the progress of the AFS petition online over the span of several days. It was apparent that a disproportionate number of the petition s signers were faculty members, farmers, and other supporters from Hawai i. That observation was confirmed when AFS met its target of 1,000 signatures. The Alliance posted a map showing where its support base resided. Nearly 7% 69 of the 1,000 signatures came from Hawai i. More have since been added. Among the signers of the AFS petition were a number of faculty members of the University of Hawai i College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, including CTAHR dean Mario Gallo.

The 69 Hawai i petitioners did not, by themselves, comprise an astounding number. More signatures were gathered from New York and California. But the signers from Hawai i did represent, per capita, the largest single group of supporters for the AFS petition worldwide.

That confirmed the plain reality that Hawai i has become, in the words of anti-biotech activists, ground zero in the biotechnology debate.

The pertinent question is this: How well are we conducting the debate? What should we do when a conflict arises between populist sentiment and science?

New scientific advances often trigger populist backlash movements. Consider Darwinism and the fierce opposition still ongoing it set off among biblical literalists, or the widespread opposition to the pasteurization of milk.

The raging debate surrounding pasteurization a century ago is instructive for the present day.

In 2001, Dr. Joseph Hotchkiss, former director of the Cornell Institute of Food Science and a science advisor to the U.S. Food & Drug Administration, wrote a paper titled Lambasting Louis: Lessons from Pasteurization. Hotchkiss noted that the application of [Louis] Pasteur s discoveries to food and agriculture was controversial, just as the application of biotechnology is today.

Hotchkiss cited four primary causes of public opposition to the pasteurization of milk.

It was reasoned that milk pasteurization was unnecessary if milk was properly handled, dairies were kept clean, and diseased animals were culled.

Dairy producers worried that pasteurization would disrupt the status quo, drive up the cost of milk, and put small producers unable to afford the process out of business.

It was argued that pasteurization adversely affected the organoleptic properties of milk, ruined its flavor and took the life out of milk.

Finally, pasteurization opponents vehemently asserted that the process diminished the nutritional quality of milk to the detriment of the health of children.

Observing parallels between the pasteurization debate of the early 1900s and the furor surrounding biotechnology today, Hotchkiss pointed to the prescient guidance supplied by Milton J. Rosenau, a pioneer in American public health. While Louis Pasteur is most associated with the thermal process that bears his name, Rosenau perfected the process of pasteurizing milk. In 1906, according to the Centers for Disease Control, Rosenau established that low temperature, slow pasteurization (140 F for 20 minutes) killed pathogens without spoiling the taste of milk, thereby eliminating a key obstacle to public acceptance of pasteurized milk. Rosenau later authored a book, The Milk Question (1912), calling for patience, public and professional education, and cooperation between commercial, government and scientific communities. He suggested all should let the facts speak for themselves.

It s worth recalling the high stakes involved in the pasteurization debate. At the dawn of the 20th century, tuberculosis claimed the lives of 160,000 Americans annually. Typhoid fever took another 25,000 lives. Infant mortality rates were horrific by today s standards. The 1900 U.S. Census reported infant mortality rates as high as 40%, with one-third of all deaths among infants. In Baltimore, 3,000 (<5 years of age) deaths per year were reported (Knox, 1906). Pathogens in raw milk contributed hugely to the death toll. And yet the milk debate raged unabated for decades in municipal councils and legislatures across the nation. Wary of a new technology, raw milk advocates successfully stalled the adoption of pasteurization at the cost of thousands of deaths. Countless politicians, too, played a part in this fatal saga.

That is why Rosenau s counsel remains on point, especially his call for patience. What the press and the political class nowadays are prone to see as a burning issue may be something that instead warrants a suspension of opinion, pending a thorough review of the facts. We don t have to rush to judgment simply because a certain ardent faction voices a concern. With due respect for that concern, we can withhold opinion and any compulsion to legislate while we gather facts and perspective.

Over a year ago, I talked to a Cornell professor named Tony Shelton, who came to the Big Island to assess the debate surrounding Hawai i County s ordinance to ban GMO crops and open-air field testing. He was concerned not just for Hawai i, but for his university and the world. He spoke with undeniable conviction. It was the mission of Cornell and, indeed, all land-grant universities, he said, to serve humanity. He meant it. He was soon on his way to Bangladesh to inspect field trials of Bt brinjal (eggplant), a staple food in that too impoverished nation. Like Cornell graduate Michael Shintaku, a native son of Ka u, and Dennis Gonsalves of Kohala, who developed the ringspot virus-resistant Rainbow papaya at Cornell, Tony knew his mission: To faithfully assess field trials in progress and their impacts on the environment and the human prospect. Tony, Michael and Dennis all signed the Science 14 petition, among many shown in a cloud of 1,200 names later assembled by the Alliance for Science. It s good to see they are not alone. Such people are a gift.